This week: an absorbingly creepy debut novel set in a decaying old mansion, plus Mary Gaitskill's excellent essay collection.

What It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky

In her powerful and incisive debut collection, Arimah shuttles between continents and realities to deliver 12 stories of loss, hope, violence, and family relationships. In “Wild,” a reckless teenage girl is sent from America to her aunt in Nigeria, only to get caught up in the life of her equally reckless cousin. “Second Chances” sees a deceased mother magically reappear in her family’s life, with mixed results, and “Buchi’s Girls” is about a widow struggling to raise two daughters while living in her sister’s house. Mother and daughter grifters deal with an unexpected pregnancy in “Windfalls,” while the collection’s futuristic title story explores a world in which mathematicians have unlocked the secrets to all humanity, allowing humans to remove emotional pain from others and disrupt the laws of nature. Arimah gracefully inserts moments of levity into each tale and creates complex characters who are easy to both admire and despise. From the chilling opening story, “The Future Looks Good,” structured like a Russian nesting doll, to the closing story, “Redemption,” this collection electrifies.

Rebel Mother: My Childhood Chasing the Revolution

A mother and her young son go looking for a liberation that verges on chaos in this luminous memoir. Political scientist Andreas (Smuggler Nation) recounts his adventures with his mother, Carol, a Mennonite turned Marxist anti-war feminist who abducted the five-year-old Peter from Michigan in 1969 during a custody dispute with her ex-husband, taking him on a years-long odyssey through South America in search of revolutionary ferment. His narrative is a vivid, picaresque tour of early-1970s left-wing counterculture: squalid communes; collective farms in Salvador Allende’s Chile; Peruvian slums, where Carol became interested in the Sendero Luminoso guerilla movement; vehement arguments about anti-establishment rectitude and fine points of Marxist theory; endless scrounging while disdaining all material desires. Mother and son both ran pretty wild (Andreas virtually raised himself in the streets while Carol sometimes bedded her parade of lovers in the room she shared with Andreas, until she married an erratic Peruvian street performer half her age), and Andreas feels both exhilaration and a longing for the stable, orderly life his father represents. Andreas’s exuberant but clear-eyed memoir paints an indelible portrait of his charismatic mother, the era’s expansive pursuit of freedom and idealistic commitment, and the toll of exhausted dreams and frayed relationships the idealists left behind.

Living in the Weather of the World

In this masterly collection of short fiction, ordinary circumstances often become consequential turning points. The book’s apt title is not that of any individual story, but a description of the terrain Bausch’s characters inhabit. A first meeting is the focus of both “The Bridge to China” and “Map Reading,” the former a midlife blind date and the latter a first meeting between unlikely half-siblings of different generations. In “Walking Distance,” a young husband hurtles into a dangerous encounter after a fight with his wife. This plot has high potential for melodrama or the trite conventions of genre fiction, but Bausch writes with such authority and transparency that the story offers surprising insight and feels entirely believable. It’s a diverse collection: a couple of the 14 stories are short enough to be deemed flash fiction, and two long stories have the depth and scope of novels. “The Lineaments of Gratified Desire” tracks the small but significant developments in a complex romantic relationship. “Still Here, Still There” stretches over 70 years in the lives of two World War II veterans and their relationship. This is a sublime collection.

Flaubert in the Ruins of Paris: The Story of a Friendship, a Novel, and a Terrible Year

Brooks (Enigmas of Identity) has written an intricate examination of Gustave Flaubert’s novel Sentimental Education against the backdrop of what is known in France as “the terrible year”—summer 1870 through spring 1871—when the country suffered defeat by Prussia, followed by bloody internal strife. This multi-layered book is the perfect companion piece while reading Flaubert’s novel. Through intimate correspondence between Flaubert and author George Sands, Brooks explores how their personal struggles during a tragic time gives perspective on “what history will do to your life.” One intriguing detail here about Sentimental Education—published in 1869—is that Flaubert believed its plot anticipated the terrible year, remarking that, had the book been better received and understood, it might have helped avert France’s upheaval. In the midst of recounting momentous historical events, Brooks includes small but meaningful details of Flaubert and Sands’s relationship and Flaubert’s efforts to “reorganize his life at age 50.” Students of Flaubert—or of history—will enjoy exploring this book’s insights into one of the 19th century’s greatest writers.

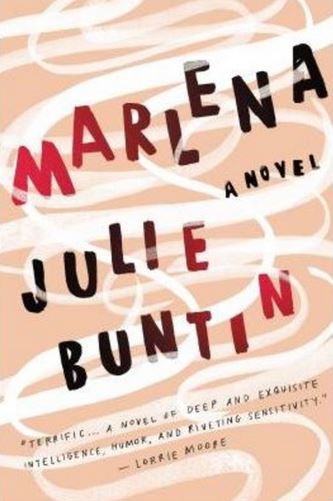

Marlena

In her impressive debut novel, Buntin displays a remarkable control of tone and narrative arc. In a keenly observed study of teenage character, narrator Catherine, 15, is miserable in the ramshackle house her newly divorced mother has bought in the dismal town of Silver Lake in northern Michigan. When she meets Marlena, her glamorous 17-year-old next-door neighbor, Cat is smitten with the euphoria of having a best friend. Buntin is particularly sensitive to the misery of adolescent angst, and Cat’s growing happiness in Marlena’s friendship runs like an electric wire through the narrative. Marlena is dangerous, however: she runs with a bad crowd, and her father cooks meth. From the beginning, we know that Marlena is irresistible, reckless, and brave; she’s a mother substitute for her forlorn younger brother—musically talented, beautiful, and doomed to die young. It’s only later that Cat understands that Marlena is the needy one in their relationship. Her bravado hides desperation; she fears she’ll never get out of Silver Lake, that she has no future, and that “there were kids like us all over rural America.” Almost 20 years later, living in New York with her husband and working at a good job, Cat is still damaged by losing Marlena. Crippled by “the pain at the utter core of me,” she takes refuge in alcohol and memories. The novel is poignant and unforgettable, a sustained eulogy for Marlena’s “glow... that lives in lost things, that sets apart the gone forever.”

The Happy End/All Welcome

In this delightful collection, poet and translator de la Torre (Public Domain) literarily extends artist Martin Kippenberger’s installation “The Happy End of Franz Kafka’s Amerika,” which she describes as “an assortment of numbered tables and office desks with pairs of mismatched chairs within a soccer field flanked by grandstands.” These formally inventive poems feature job notices, briefs, interview transcripts, and an office furniture inventory; readers will feel like they have stumbled into a job fair in some alternate universe. For example, a manager explains to a consultant that “We don’t really have a CEO. We have an Artistic Director. The office chairs surrounding us are ghosts of obsolete hierarchies. We keep them as reminders of what can go wrong.” De la Torre presents everything with a straight face, even a hilariously jargon-riddled posting for someone to give a presentation on the value of humor in the workplace. She warps and exaggerates the more ridiculous elements of professional etiquette, start-up culture, and corporate language in ways that encourage readers to look deeper into our work spaces to see how strange they really are. Perhaps, as de la Torre suggests in “Ad Copy,” “The mantra of The Happy End / All Welcome might be that slapstick speaks louder than words, the work imploding with what it implies.”

A Fever of the Blood

Murder, potions, curses, an asylum, a devastating snowstorm, and late-Victorian manners and morals—all figure in de Muriel’s delicious witches’ brew of a mystery, the worthy sequel to 2016’s well-received The Strings of Murder. In this outing, the mismatched detectives Insp. Ian Frey and Adolphus “Nine Nails” McCray—“a lanky Londoner who fancies himself a duke, travelling with a scruffy Scotsman who wears ridiculous clothes,” as one character puts it—chase an escapee from an asylum who has poisoned his nurse with strychnine. The duo start in Edinburgh and end on the desolate moor of Pendle Hill, infamous home of the real-life Lancashire witches, who were executed in the 17th century. The well-paced and suspenseful plot hurtles readers through a centuries-old conspiracy coming to a head in 1883, marked by eerie questions of occult powers. But the most impressive aspect of the novel is its detailed, vivid characters, driven by powerful emotions and full of surprises.

American War

El Akkad’s debut novel transports us to a terrifyingly plausible future in which the clash between red states and blue has become deadly and the president has been murdered over a contentious fossil fuels bill. In 2074, Sarah T. Chestnut—called Sarat—comes of age in the neutral state of Louisiana, where she is slowly drawn into the conflict after the death of her father, performing guerrilla operations for the South. Soon she is enmeshed in a resistance movement masterminded by the Dixie militants operating along the Tennessee River, venturing into quarantined South Carolina battlegrounds and Georgia shantytowns alongside spies, assassins, and revolutionaries, like the commanding Adam Bragg and his Salt Lake Boys. Sarat finds brief happiness with Layla, a displaced bar owner from Valdosta, Georgia, but this is only the beginning of Sarat’s war, as she is interred in the nightmarish Camp Saturday before being exiled in the wake of a devastating plague. Now an old and broken woman, Sarat must seek redemption in the wreckage of the New World. Part family chronicle, part apocalyptic fable, American War is a vivid narrative of a country collapsing in on itself, where political loyalties hardly matter given the ferocity of both sides and the unrelenting violence that swallows whole bloodlines and erodes any capacity for mercy or reason. This is a very dark read; El Akkad creates a world all too familiar in its grisly realism.

Somebody with a Little Hammer: Essays

This collection of essays spanning two decades has the same fearless curiosity about the human psyche that Gaitskill (The Mare) exhibits in her fiction, along with the same unerring precision of prose. The broad range of her reviews, which cover art and literature from the Book of Revelations to Gone Girl, are united by her demand for complexity, her fascination with “enchantment and cruelty” (the title for her piece on J.M. Barrie), and her disdain for sentimental complacency. Early reflections tease and knead language into towering baroque shapes, but essays such as “The Bridge,” on her visit to Saint Petersburg, and the astonishing “Lost Cat,” on losing her pet, Gattino, settle down to the work of attentive, metaphor-rich descriptions. In later essays, Gaitskill’s dryness veers toward the acerbic, shearing through the reductive and the bowdlerized. Even those essays which start with the broadest of subjects—myth, religion, literature—repeatedly turn inward, drawn by Gaitskill’s interest in complicated inner landscapes, her favorite theme of “the innately mixed, sometimes debased nature of human love,” and her unyielding “moral empathy” for the perversity of the human condition. The surprising, nimble prose alone is a delight, and the pages burst with insight and a candid, unflinching self-assessment sure to thrill Gaitskill’s existing fans and win her new ones.

Prussian Blue: A Bernie Gunther Novel

Edgar-finalist Kerr’s stunning 12th Bernie Gunther novel (after 2016’s The Other Side of Silence) races along on two parallel tracks. In the first, set in 1956, Bernie, who’s been working as a hotel concierge in Cannes, flees France because he bailed out of performing a hit for Stasi chief Erich Mielke, killing a Stasi agent in the process. The hazardous journey takes him by train, bicycle, and foot toward West Germany. In the main narrative, set in April 1939, SS Gen. Reinhard Heydrich, Bernie’s boss, orders him to Berchtesgaden, Hitler’s mountain retreat. A sniper has fatally shot Karl Flex, a civil engineer in Martin Bormann’s employ, on the deck of Hitler’s villa, the Berghof. Bernie has mere days to solve the crime before Hitler returns to Berchtesgaden to celebrate his 50th birthday. Trying to identify Flex’s killer and bring him to justice proves to be the least of Bernie’s worries. Kerr once again brilliantly uses a whodunit to bring to horrifying life the Nazi regime’s corruption and brutality.

The Financial Diaries: How American Families Cope in a World of Uncertainty

This sharp-eyed, sympathetic study from Morduch, a public policy and economics professor, and Schneider, a financial services company vice president, has a compelling new angle on the effects of long-term financial instability on working-class families. The authors’ focus is on cash flow and how it can reveal instability that’s not otherwise obvious from simple income information. They designed the titular financial diaries by recording a total financial picture for each of 235 households in five states: dollars earned, spent, and received in government entitlements. The study shows how cash-flow uncertainty prevents people from sticking with long- or even short-term financial plans. Using the narratives of a handful of survey respondents—including a casino card dealer and a performing arts teacher—the authors discuss various coping methods: saving, borrowing, and drawing on communities and networks. They also examine how pervasive financial uncertainty drains people’s time and energy, citing a 2014 survey in which 92% of respondents said they would prefer economic stability to extra income. This is a must-read for anyone interested in causes of—and potential solutions to—American poverty.

The Draw: A Memoir

In this powerful, jarring memoir, author and critic Siegel (Against the Machine) painstakingly maps the bitter familial legacies that shaped him. Suspended between parents with artistic aspirations—an ineffectual, self-effacing jazz pianist father and a histrionic, failed actress mother—Siegel bombed as a student and low-wage worker, even as his immersion in literature convinced him that he was destined for greatness. His attempts to escape the vortex around his childhood home propelled him to college in the Midwest and later to Norway, where he finally began to create a viable self. Eschewing the standard minimalism of the literary memoir, Siegel explores the psychological complexity of his family romance in layered prose, in particular the impossible demands of a mother who shrieks across the pages like a monstrous suburban hybrid of Joan Crawford and Blanche Dubois. Siegel’s vivid portrayal of this turbulent woman is so intense that the narrative can falter when she’s offstage, with friends, lovers and even his father fading in her absence. Siegel’s strong focus on psychological depth rather than the visible remakes his familiar journey from American boy to man into something strange, disturbing, and wonderful.

God’s Red Son: The Ghost Dance Religion and the Making of Modern America

Warren, a professor of U.S. history at the University of California, Davis, provides an engrossing, readable, and carefully researched history plotting the rise, spread, and continued life of the Ghost Dance among Native Americans. Since its rise in 1890 and sudden, violent suppression at Wounded Knee, the history of the Ghost Dance has focused on its return to past practices, the promise of a land free from whites, and protection in battle. Warren does not dismiss the influence of forced resettlement and broken treaties made with Native American communities, but he persuasively argues that Native American adherents focused more on integrating with Euro-American economy and used the Ghost Dance to maintain their native culture and “Indianness.” Key figures shape his narrative, including the prophet Wokova in Nevada, whose visions sparked the movement; Short Bull, the Lakota who brought it to the Plains; and James Mooney, the white anthropologist who recorded it and shaped all subsequent scholarship. Warren ties together seemingly unrelated strands to give a clear sense of the convulsing changes and challenges of the last decade of the 19th century. The work will delight fans of well-written history and appeal to historians of the West, Native Americans, and religion.

Foxlowe

In Wasserberg’s absorbingly creepy debut, a young girl grows up in an isolated commune at the edge of a Stonehenge-like group of standing stones. Born in the decaying old mansion that is the home of a “ragtag group” called the Family, the girl known only as Green tells her story from her own limited point of view, leaving the reader to infer much that the narrator can’t understand. It’s a literary perspective much like that of Emma Donoghue’s Room, and used to equally chilling effect here. Green’s troubled mother, Freya, one of the group’s founders, alternately smothers her daughter with affection and punishes her in grisly ways to get rid of “the Bad.” When a baby the Family names Blue is brought in from the feared outside world, Green is wracked with jealousy, and the stage is set for the downfall of the already distressed commune. Though the ending of the novel is violent, that horror arises naturally out of what precedes it. The narrator’s voice is equal parts naive and wise; Wasserberg has a gift for allowing the reader into this world inch by inch while playing up its claustrophobic nature, as well as the aspects that make Green susceptible to its enchantments.