Cristina Rivera Garza's astounding and mind-bending novel The Iliac Crest is about two women visiting an unnamed narrator at his oceanside home and gradually unraveling his life, fractures his sense of reality and shifting his understanding of his own gender. Rivera Garza highlights 12 female authors from the Spanish-speaking world.

Some of them are cult writers in their respective countries; some have gained recognition across the Spanish-speaking world but have yet to be fully accounted for in English; some are translated into several languages, figuring prominently in trans-border literary conversations in languages other than English; most defy easy classification; all deserve a place in your reading list. This is but a small selection of the many women writers from the Spanish-speaking world who have ceaselessly questioned the status quo, refusing to comply with gender and other hierarchies. Their voices are more necessary than ever. Long live too their fearless and irreverent translators!

Cristina Peri Rossi

Exile from Uruguay has played a key role in the writing life of Cristina Peri Rossi (Montevideo, 1941)—a portent of a writer who has tackled with equal mastery novels, short stories, essays, and poetry. While some of these works have been diligently translated into English (the most recent example is State of Exile, translated by Marilyn Buck for City Lights in 2008) we don’t talk nearly enough about the work of this luminous writer whose merciless attention to desire—lesbian desire—and early proclivity for formal experimentation may be about to find its best audience. The shifting worlds of Peri Rossi may well be the true home that the migrants, misfits, runaways, and uprooted men and women of our era are looking for.

Elena Medel

Sometimes women writers have to do it all, and at an early age. Elena Medel (Córdoba, 1985), wrote and published Mi primer bikini (translated by Lizzie Davis as My First Bikini for Jai Alai Books in 2016) at age 16, winning the prestigious Andaluzia Prize for young poets. Three years later, she launched La Bella Varsovia, an independent publishing house that has since then given shelter to poetry “that works closely with language, that is alert to the fluctuations of reality, that is written mostly, although not only, by women.” A cultural activist and a champion for women´s rights, Elena Medel´s approach to that quintessential piece of clothing—the bikini—is both delicate and raw, embracing the vicissitudes of early womanhood.

Sara Uribe

Sara Uribe (Querétro, 1978) has authored what is perhaps the poem of an entire generation: Antígona González (translated by John Plucker for Les Figues Press in 2015). Originally published by SurPlus, an independent press established in Oaxaca, Mexico, Antígona González roared into the world in 2011, giving words—broken, merciful, full of rage—to the low intensity war Mexico has undergone for more than a decade. Fierce, urgently political, and human to the core, this documentary poem summons the dead and brings them to our tables, reminding us that the day we cease sharing memory and language with them, we ourselves will become loss, vanished sign, mere oblivion.

Rosario Castellanos

A writer of multiple talents, Rosario Castellanos (Mexico, 1925-1974) wrote memorable social novels in which modernity cruelly conflated with indigenous Mexico (such as The Book of Lamentations, translated by Esther Allen), as well as satirical poems that demonstrated she was not afraid of laughing at herself. Her “Eternal Feminine,” a theater play included in The Rosario Castellanos Reader, translated by Maureen Ahern for Texas University Press in 1988, is a veritable tour de force. At a beauty parlor, women´s heads remain under sci-fi-like hair dryers as they dream with an alternative history of the world. The murmurs of Eve, La Malinche, or Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz contribute to a scathing and relentless subversion of gender stereotypes, transforming the main character forever. A feminist at heart, Castellanos died accidentally while trying to turn on a lamp.

Marosa di Giorgio

A rara avis of Latin American letters, Marosa di Giorgio (Salto, 1932-Montevideo, 2004) is best known for her prose poems. Infused with eroticism and populated by animal and vegetal life in constant transmutation, her writing renders the world anew—and easy prey to both hallucination and freedom. In I Remember Nightfall, translator Jeannine Marie Pitas has beautifully delivered di Giorgio´s vision—rather, her intimation: natural and supernatural creatures exchange secrets and yearnings here, by our side. As di Giorgio´s dirty and golden lions that first haunted and then entered the house of an obscure grandmother, her writing circles our lives, threatening and intriguing, with peculiar syntax and arresting beauty.

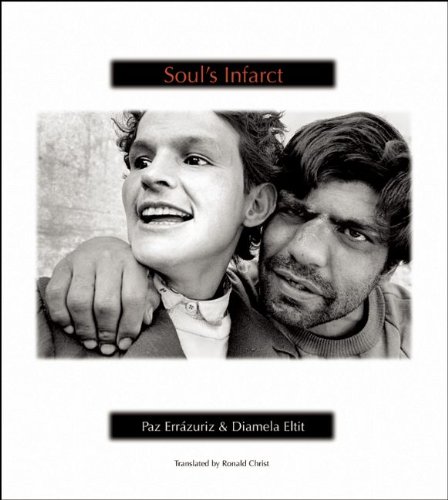

Diamela Eltit

While it´s generally accepted that love is a form of madness, are we as ready to admit that the mad can fall in love? In Soul´s Infarct, translated by Ronald Christ for Helene Lane Books in 2009, Diamela Eltit (Santiago, 1949), Chile´s foremost experimental writer, has opened the doors of a provincial psychiatric institution not far from Santiago where poor men and women live, walk through the corridors, stare up to the sky, and indeed, fall in love. Triggered by the photographic images of Chilean artist Paz Errázuriz—which depict inmates in a dignified manner—Eltit crosses literary genres to question the relationship between love and madness, and their connection with marginality and power. Eltit has famously embraced writing as a political practice—and this is political writing at its intimate best.

Leonora Carrington

Leonora Carrington (Lancashire, England, 1917-Mexico City, 2011) is better known as a painter—and a surrealist one at that, much to her chagrin. Some may be familiar with her long exile in Mexico, initiated in 1943, while others may still remember that Marx Ernst became her sentimental partner when she was about 20 years old (and he 47). Still, few are aware even now that she was an incisive, fiercely independent writer of wild imagination. In the many worlds she created, and we can take a peek at them in The Complete Stories by Leonora Carrington. introduction by Kathryn Davis (Dorothy Project, 2017), human and non-human elements interact intimately, often exchanging places. Written originally in several languages—Spanish included—Carrington´s stories use irony as much as fantasy to unlock the mysteries of the soul and to mock power with her own unique brand of eco-feminism avant la lettre. And how else could we describe the horse-woman´s fleeing from human society, opting instead for a world of plants and beasts?

Laura Solórzano

Laura Solórzano (Guadalajara, 1961) leads a discreet life in her native Guadalajara, where she offers writing workshops at a local school. The publication of Lip Wolf, aptly translated by Jen Hofer for Action Books in 2007, unveiled what few knew: that her demeanor might be quiet, but her inner life is tumultuous, brimming with excitement about the materiality—the fleshiness—of words and their multiple connections with human and non-human life altogether. Under her gaze, the mere act of feeding a child with a wooden spoon appears as a threatening choreography of angst and love. As poet Mónica de la Torre asserts, Solórzano´s poems “provide us with stunning soundings of that which resists remaining still in the form of images.”

Inés Arredondo

Inés Arredondo (Culiacán, 1928-Mexico City 1989) is almost a secret in Mexican letters. Like her most famous contemporary Juan Rulfo or the lesser known but equally gifted Josefina Vicens, Arredondo published few books in her lifetime. In Underground River and Other Stories, translated into English by Cynthia Steele for University of Nebraska Press in 1996, Arredondo delves into the dark side of gendered desire. This masterful collection of short stories depicts a world in which love and destruction seem interchangeable. Here women fall pray to the desire for younger boys while powerful, decrepit men roam fields and parties alike seeking to devour the flesh of young girls. Perhaps Arredondo was not only portraying the worlds she closely observed in both her native Culiacán in northern Mexico and the capital city where she died; perhaps she was looking into the future, and writing about our time.

Julieta Campos

Had she chosen to live in the United States, and not Mexico, after her exile from Cuba, Julieta Campos (Habana, 1932-Mexico City, 2007) could have been called an experimental writer in her own right. In both She Has Reddish Hair and Her Name is Sabina, trans. by Leeland H. Chambers, (University of Georgia Press, 1993), and The Fear of Losing Eurydice (Dalkey Archive, 1993), Campos deftly plays with form, altering the architecture of page and the flow of narrative. While her books tell a story (often a love story) they question and subvert the cultural automatisms and literary formats in which stories are customarily told, producing cross-genre work avant la lettre. Brainy and beautifully rendered, her books investigate the operations of desire and memory and they way in which they leave traces, and wounds, in both body and society.

Gabriela Wiener

No other writer in the Spanish-speaking world is as fiercely independent and thoroughly irreverent as Gabriela Wiener (Lima, 1975). Constantly testing the limits of genre and gender, Wiener´s work as a cronista (which roughly translates, but is by no means a direct synonym, of nonfiction writer) has bravely unveiled truths some may prefer remain concealed about a range of topics, from the daily life of polymorphous desire to the tiring labor of maternity. The books of this prolific writer and unabashed feminist are yet to be translated into English (I hear Restless Books might have news for us in this regard), but meanwhile you can have your Wiener fix here.

Marta Aponte Alsina

Marta Aponte Alsina (Cayey, 1945), a ferociously intelligent writer from Puerto Rico, has yet to be made available in English. Author of novels and short story collections, as well as of insightful literary criticism, Aponte works with documents and dreams, obsessions and interviews alike to write books of incredible beauty that defy genre classification. Loosely based on the life of poet William Carlos Williams and his relationship with his Puerto Rico-born mother, La muerte feliz de William Carlos Williams fuses memories of Aponte´s own life with her reading of poems, novels, and biographical material about and by William Carlos Williams to explore recurrent topics in her own writing: the foreigner´s gaze, the re-writing (and subverting) of canonical texts, the extended linkages of Puerto Rican culture across the United States, and the neglected voices of women. 1955: Lavander Mist is a short story translated by Jeremy Osner in collaboration with Scott Esposito for The Acentos Review.