This week: a novel set in a scary AI-overrun 2083, plus a history professor in her 60s goes to art school.

Rendezvous with Oblivion: Essays

A decade of fraud, exploitation, and hypocrisy gets mercilessly dissected in these caustic essays. Journalist and historian Frank (Listen, Liberal) gathers pieces published in Harper’s, the Guardian, and elsewhere since 2011, surveying the cultural camouflage that disguises the predatory workings of capitalism. He attacks many juicy targets, including the callous interpersonal psychology of rich people; the faux-folksiness of fast-food restaurants that pay starvation wages; journalism’s plunge, led by conservative media mogul Andrew Breitbart, into fake news and mindless caricature; the defunding of the humanities at universities and academics’ defense of those fields as incubators of business acumen; reactions to Steven Spielberg’s film Lincoln that lionized its depiction of political corruption as bipartisan “compromise” to which real-life politicians should aspire; and the George W. Bush Presidential Library’s efforts to gloss over war, Hurricane Katrina, and economic collapse with an exhibit on “Laura and the twins and all the fun they had.” In several trenchant pieces probing Donald Trump’s rise, Frank avoids simplistic claims of voter bigotry and instead emphasizes issues of trade, economic decline, and the Democrats’ abandonment of the working class for a politics of centrist neoliberalism. Frank’s combination of insightful analysis, moral passion, and keen satirical wit make these essays both entertaining and an important commentary on the times.

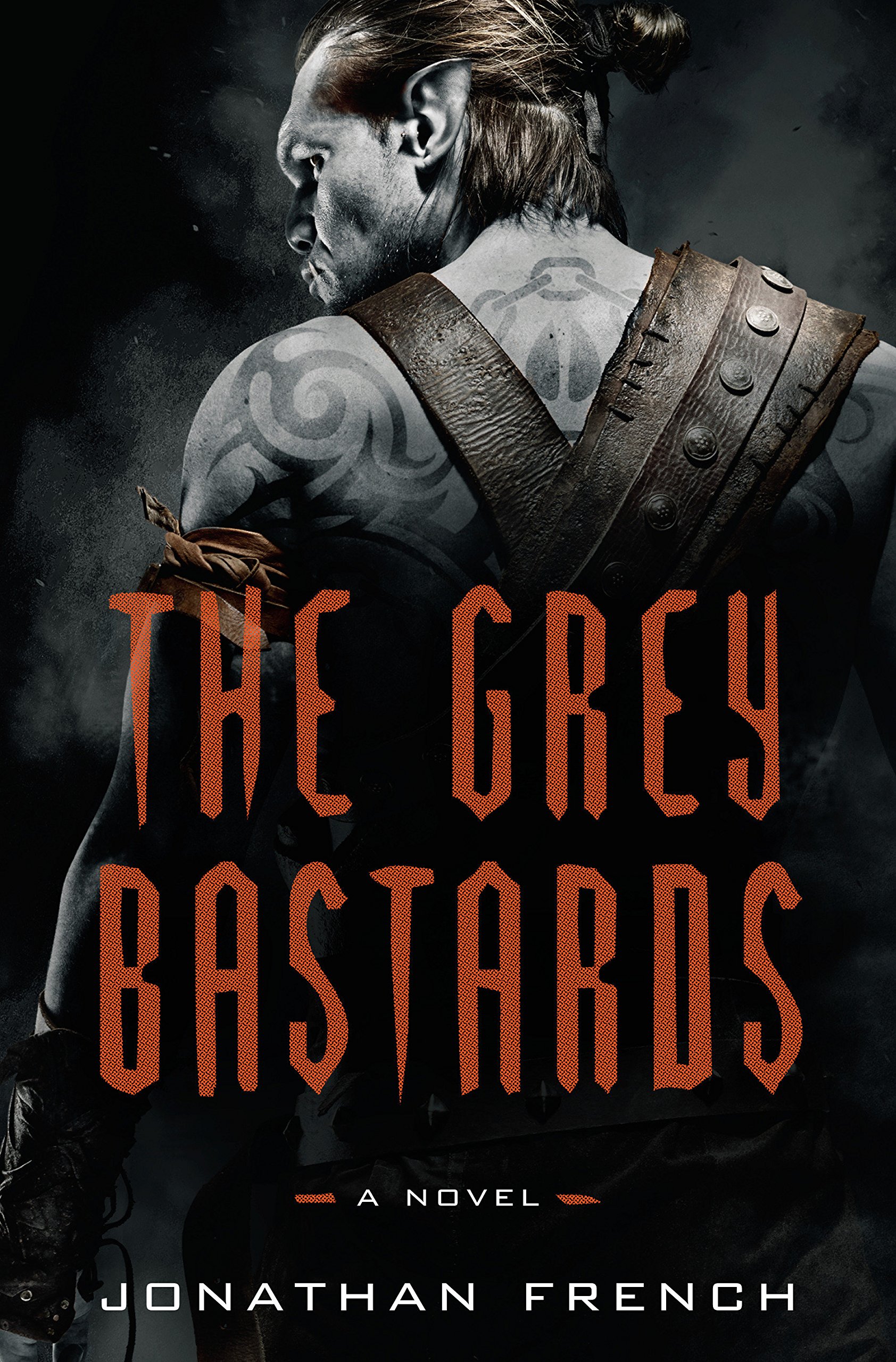

The Grey Bastards

This terrific and highly original epic fantasy debut focuses on a single small fighting unit: the boar-riding half-orc war band known as the Grey Bastards, “forged in the heat of Ul-wundulas, tempered by the pressure of the badlands, and quenched in the brackish water of life on the hoof.” The coarse nature of French’s half-orcs is immediately on display in the opening scene, in which Grey Bastards Jackal, Oats, and Fetching face off against a squad of human cavalry at the local brothel. A raid by full-blooded orcs, the arrival of an unknown half-orc wizard dubbed “Crafty,” and a confrontation in a nearby swamp with the Sludge Man and some “giant, featureless leeches made of tar” are just the beginning for Jackal and his mixed-gender crew. Meanwhile, the band’s leader, Claymaster, has been crafting nefarious schemes with unclear ends. The plots within and around the Grey Bastards add elements of mystery to the scenes of bloody combat and weird magics. French’s prose, appropriately lowbrow among the half-orcs, is almost poetic at other times. His half-orcs, halflings, centaurs, and others have rich histories and folklore, giving the work depth while never getting in the way of the fun. This is excellent fantasy fare on all levels.

Call Me American: A Memoir

War-torn Somalia is the unlikely incubator for an immigrant success story in this wrenching yet hopeful autobiography. Iftin was five years old in 1991 when a decadeslong civil war engulfed the Somali capital of Mogadishu; his family witnessed massacres by militias, survived death marches, and endured years of starvation. His one escape from grim reality was a movie theater where he learned English watching American action movies, and his enthusiasm for the wealth, freedom, and rough justice depicted in them earned him the nickname “Abdi American.” That spelled trouble, however, when the rise of Islamic extremism brought harsh religious strictures—he was flogged for going to the beach with a girl—and attacks on anyone associated with America. A chance 2009 encounter with an American reporter got him a gig doing radio dispatches for NPR, and more Islamist threats; after his house was bombed, he fled to the enclave for persecuted Somalis in Kenya, and finally, after navigating the labyrinth of U.S. immigration rules, moved to rural Maine, where he now works as a translator. Written in limpid prose, Iftin’s extraordinary saga is not just a journey of self-advancement but a quest to break free from ethnic and sectarian hatreds.

A Stitch in Time

Tautly written yet surging with emotion, this debut novel is set in 1927 Vermont, where an 11-year-old girl contends with wrenching past, present, and (she fears) future loss. After her mother died in childbirth, Donut (nicknamed for the confection that alone could lull her to sleep as a baby) was raised by her father, whose recent accidental death brings a double-edged sadness: not only does Donut miss him immensely, but without the memories he shares, “She’d lost her mother for good, now.” Her stodgy aunt’s decision that Donut move to Boston to live with her outrages the girl, who recognizes that leaving her village means “I’ll be leaving Pops, too. He’s here, everywhere.” In protest, Donut runs away to an abandoned cabin, but she sinks her father’s homemade boat midlake and inadvertently sets fire to the shack. Kalmar introduces a delightfully intricate character in Donut, whose passions include bird taxidermy, memorizing tidbits from the atlas Pops gave her, and her friendships with affectingly portrayed Vermonters. The author leaves readers knowing that her insightful, articulate, and wry heroine will land—solidly—on her feet. Ages 8–12.

Number One Chinese Restaurant

With echoes of Stewart O’Nan’s Last Night at the Lobster, Li’s insightful debut takes readers behind the scenes of a Chinese restaurant, the Beijing Duck House, in Rockville, Md. Jimmy Han, son of the restaurant’s deceased original owner, runs the business but is trying to sell it to transition to a more upscale venue, the Beijing Glory, an Asian fusion restaurant on the Georgetown waterfront. Jimmy and his older brother, Johnny, have had a running argument about the direction of the Duck House—Johnny wants the restaurant to remain traditional—since the death of their father. Their manager, Nan, and Ah-Jack, a waiter, have been friends for 30 years but lately have become romantically involved. Meanwhile, Nan’s troubled 17-year-old son, Pat, a dishwasher, and Johnny’s disaffected daughter, Annie, a hostess, have been having not-so-secret sex in the storage closet. And hovering over all of them is Uncle Pang, a mysterious, nine-fingered godfather who might hold the key to their futures. Despite the novel’s leisurely plotting, Li vividly depicts the lives of her characters and gives the narrative a few satisfying turns, resulting in a memorable debut.

The Great Believers

Spanning 30 years and two continents, the latest from Makkai (Music for Wartime) is a striking, emotional journey through the 1980s AIDS crisis and its residual effects on the contemporary lives of survivors. In 1985 Chicago, 30-something Yale Tishman, a development director at a fledgling Northwestern University art gallery, works tirelessly to acquire a set of 1920s paintings that would put his workplace on the map. He watches his close-knit circle of friends die from AIDS, and once he learns that his longtime partner, Charlie, has tested positive after having an affair, Yale goes into a tailspin, worried he may also test positive for the virus. Meanwhile, in 2015, Fiona Marcus, the sister of one of Yale’s closest friends and mother hen of the 1980s group, travels to Paris in an attempt to reconnect with her adult daughter, Claire, who vanished into a cult years earlier. Staying with famed photographer Richard Campo, another member of the old Chicago gang, while searching, Fiona revisits her past and is forced to face memories long compartmentalized. As the two narratives intertwine, Makkai creates a powerful, unforgettable meditation, not on death, but rather on the power and gift of life. This novel will undoubtedly touch the hearts and minds of readers.

The Robots of Gotham

Debut author McAulty, an expert in machine language learning, extrapolates a scary AI-overrun 2083 that’s only a few steps removed from today’s reality. This massive and impressive novel is set in an America that outlawed the development of artificial intelligence and quickly lost a short and bitter war against robot-led fascist countries. Most of America is now occupied by Venezuelan “peacekeeping” forces. The story is narrated tastefully and with self-deprecating humor by Barry Simcoe, a 30-something Canadian CEO recently arrived in Chicago to close some international technology deals. Shocked by what he sees, he immediately plunges into 10 days of complicated rescue sorties against a backdrop of urban devastation and corruption. He saves a wounded diplomat robot, allies himself with a Russian biowarfare specialist who’s developing an antidote for a virus intended to wipe out the human race, and risks his life to adopt a starving Rottweiler. For romantic appeal, he variously saves and is saved by Mackenzie Stronnick, a gorgeous machine-hating Chicago realtor; tough Venezuelan sergeant Noa Van de Velde; and enigmatic masked robot Jacaranda. Though the technology-rich plot loses a bit of its savage verisimilitude as it progresses, McAulty maintains breathless momentum throughout. Readers will hope for more tales of this sinister future and eagerly pick up on hints that Barry and his companions may continue their exploits.

Old in Art School: A Memoir of Starting Over

A history professor in her 60s takes a break from teaching at Princeton University to go to art school in this witty and perceptive memoir. After enrolling at Rutgers University in the fall of 2007, Painter (The History of White People), quickly immerses herself in her drawing and painting classes as she wryly observes her younger classmates “upholding art-school sartorial drama in bright yellow hair and piercings.” She notes that her fellow students, who know far less of the world than she does, are better painters, and she explores how her thinking as a historian hobbles her as an artist. Her “20th century eyes favored craft... narrative and meaning” while her 21st century classmates and teachers preferred the “DIY aesthetic” and appropriation from popular culture (e.g., cartoons, pornography). Painter goes on to attend graduate school at the Rhode Island School of Design, where she feels like a misfit as the oldest—and only black—student in her class, and is also unappreciated for her intellectual sophistication, though she ultimately develops her own aesthetic and confidence in her work. This is a courageous, intellectually stimulating, and wholly entertaining story of one woman reconciling two worlds and being open to the possibilities and changes life offers.

Confessions of the Fox

Academic intrigue meets the 18th-century underworld in Rosenberg’s astonishing and mesmerizing debut, which juxtaposes queer and trans theory, heroic romance, postcolonial analysis, and speculative fiction. The story appears in the form of an ostensibly historical document and lengthy discursive footnotes. In a 2018 not entirely recognizable as our own, transgender university professor R. Voth happens upon an apparently unread 1724 manuscript entitled “Confessions of the Fox.” It purports to be the memoirs of real-life 18th-century British folk hero Jack Sheppard, whose crimes and jailbreaks transfixed his contemporaries and inspired works including Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera. But this Jack was born female, falls in love with a mixed-race sex worker, and clashes with a ring of conspirators attempting to monetize a potentially priceless masculinizing elixir. Some of the footnotes Voth appends as he edits the manuscript cite scholarly references. Others are glosses on the 18th-century slang with which the swashbuckling and often sexually charged action is narrated. Still others recount Voth’s own travails: broke and lonely, he must also contend with a shadowy publisher-cum-pharmaceutical company hoping to cash in on the manuscript’s value. Rosenberg is an ebullient and witty storyteller as well as a painstaking scholar. Like the Sheppard of most earlier tellings, his Jack is an entertaining “artist of transgression” who sheds shackles with ease. Yet the novel is most memorable when evoking the pain behind such liberations: the constraints of individual and collective bodies, and the infinite guises of the yearning to break free.

The Anomaly

Fans of the paranormal thrillers of Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child will relish this superior debut from screenwriter Rutger, who makes the fantastic seem less so by dint of his self-aware, flawed lead and his ability to inject gallows humor into tense situations. Nolan Moore hosts The Anomaly Files, a YouTube show dedicated to exploring unexplained phenomena, but he and his team hope for bigger things after the Palinhem Foundation—whose mission is truth, according to a foundation representative who goes by the name Feather—sponsors an expedition that could land the show a cable deal. Nolan and his colleagues, accompanied by Feather, travel from Los Angeles to the Grand Canyon to attempt to locate a cavern allegedly found by an early-20th-century expedition sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution, which later suppressed the expedition’s discovery of “evidence that North America was visited in eldritch times by another culture.” Nolan and gang succeed in finding the cavern, only to encounter incredible—and terrifying—objects that place their lives in jeopardy. Rutger milks every ounce of suspense from his plot.

Not the Girls You’re Looking For

In this YA debut, Safi explores the internal struggle of having to “talk to more than one world, simultaneously.” Lulu considers herself both American and Arab (her father is a Muslim immigrant, her mother from Louisiana), but to many of her classmates, she’s only Arab (and therefore a terrorist). Meanwhile, she fails to meet her Muslim family’s cultural standards. Lulu is a girl who defies stereotypes: a Muslim who celebrates Ramadan, drinks, smokes, and loves to hook up with boys. Safi’s prose style has a lively staccato rhythm that captures Lulu’s spirited nature, which can easily slip into impetuousness. In addition to Safi’s focus on multicultural identity, her story provides a candid perspective on female friendships that are full of conflict, love, and angst. Through her character of contradictions, Safi offers a refreshing perspective on conformity and the path to self-actualization. Ages 13–18.

Rainy Day Friends

Shalvis entices with sensuous romance and a touch of humor as one woman’s journey of healing takes her to a California winery. Lanie Jacobs is devastated first by the death of her husband, Kyle, and then by the discovery that he was married to other women while married to her. Looking for a change, she takes a job as a graphic artist at the Capriotti Winery. Lanie is surprised and reluctantly charmed by the boisterous and welcoming Capriotti family members, who are led by matriarch Cora. Though Lanie is wary of men, she cannot help her attraction to Cora’s son, Mark, a single deputy sheriff with two adorable twin daughters. As Lanie and Mark are irresistibly drawn to each other, their romantic interludes sizzle with passion, though the wounds from their pasts leave them reluctant to seek a lasting relationship. Lanie adjusts to life with the members of the Capriotti family as she befriends new employee River Green, a pregnant young woman with secrets of her own. Lanie struggles to decide whether she can remove the barriers around her heart for a chance at true happiness. With a fast pace and a lovely mix of romance and self-discovery, Shalvis’s novel is chock-full of magnetic characters and seamless storytelling, rich with emotions, and impossible to put down.

The Shepherd’s Hut

The latest from Winton (Breath) is a mournful and fast-paced journey into the life of a young man on his own. Left by himself after the death of his violent, hateful father, teenager Jaxie Clackton sets out deep into the empty saltlands of Western Australia, searching for peace and solitude. As he heads slowly north, intending to return to the only person who’s ever loved him, he hunts kangaroo and stays away from the highways, carrying little but his rifle, water bottle, and binoculars. But soon Jaxie meets exiled Irish Catholic priest Fintan MacGillis. He must decide if he can trust MacGillis’s offer of rest and help—and then whether he will continue on to his original destination. The two fall into a rhythm, and possibly a friendship, until they discover something dangerous in the desert that threatens their safety. Winton’s novel is alive with pain and suffering, but it is also full of moments of grace and small acts of kindness. Gorgeously written and taut with eloquent, edgy suspense, Jaxie’s journey is a portrait of young manhood amidst extreme conditions, both inward and outward.