Eyes

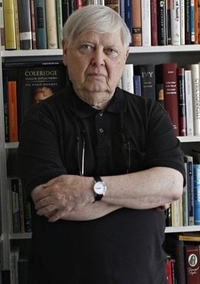

William H. Gass. Knopf, $26 (256p) ISBN 978-1-101-87472-1

An “eye,” the epigraph to Gass’s (Middle C) new story collection informs us, is “the point where an underground spring suddenly bursts to the surface.” It is evident from these tales that the 90-year-old’s creative fount is far from dry. The book opens with two novellas, each of which coaxes sublimity out of wry, misanthropic portraits. In the first, “In Camera,” a gruff art dealer zealously guards his invaluable photography collection from prying eyes. He is less interested in profits, or people, than luxuriating in the infinite grays of his black-and-white prints and their representation of the “world as it is rescued by the camera and redeemed.” Like his On Being Blue, the second novella, “Charity,” demonstrates Gass’s extraordinary ability to riff on the philosophical, spiritual, and earthly materializations of an idea. Here a young lawyer besieged by panhandlers, fund-raising groups, and scam artists all seeking contributions ruminates on “creation’s constant need for charity.” In a free-flowing, associative, and often ribald narrative, Gass anatomizes a cultural phenomenon that only vaguely resembles the charity St. Paul lauded in his famous epistle. The stories that follow don’t reach the same heights. Particularly belabored are two comic exercises, “Don’t Even Try, Sam,” in which a prop piano narrates its experience on the set of Casablanca, and “Soliloquy for an Empty Chair,” in which a barber shop’s folding chair divulges the secrets of its sedentary life. Much better are the previously unpublished “The Toy Chest,” alternately acerbic and nostalgic, and “The Man Who Spoke with His Hands,” which balances its whimsy with a vague sense of menace in an account of a music professor whose expressive hands have a life of their own. For most of this collection, Gass proves himself a master diviner, able to tap into the deepest and most mysterious reservoirs. (Oct.)

Details

Reviewed on: 07/13/2015

Genre: Fiction