I.N.J. Culbard's graphic adaptation of H.P. Lovecraft's The Case of Charles Dexter Ward is his second, following 2012's At the Mountains of Madness. Culbard walks us through the process of retelling Lovecraft, while still retaining the author's trademark style and mood.

|

| Click image to see a bigger version |

|

| Click image to see a bigger version |

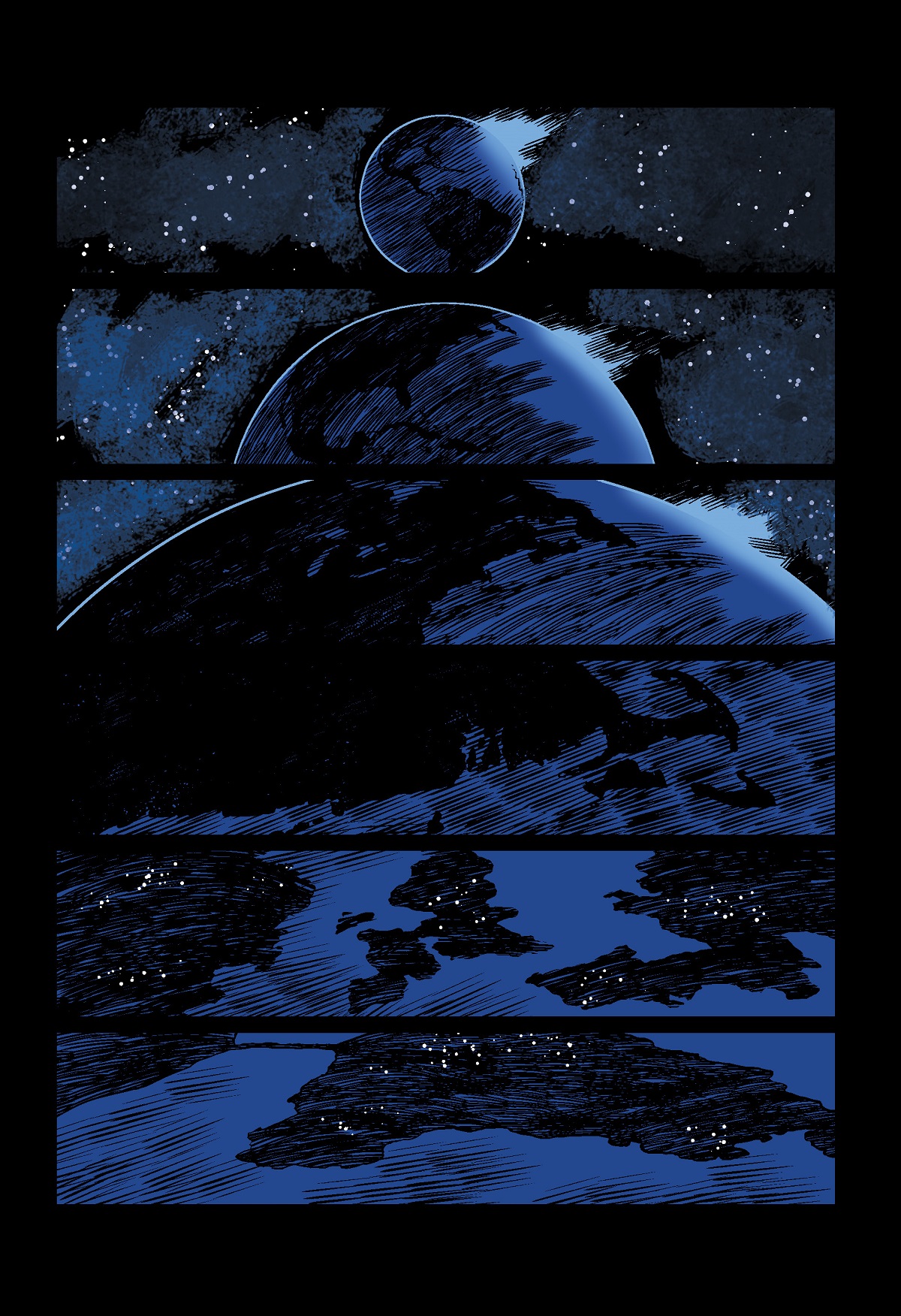

The book opens in space. We see a crescent of light. It is the earth, small against the dark ocean. And then, as we turn the page, we zoom in closer and closer to the personal level, to the heart of the story—a scene in which Charles Dexter Ward has seemingly escaped his room at an asylum.

One of the key things about adapting Lovecraft is the sense of scale. Lovecraft writes about cosmic horror, the horrors of the universe, which are far, far greater than us. We are small and we are insignificant, and yet Lovecraft manages to make those horrors significant to us. He writes about understanding, the lack thereof, and the horror in the darkness of our own benighted ignorance—things beyond our comprehension and beyond our control.

Lovecraft’s protagonists are often detached individuals, and there is an ever-present sense of fragility and futility. Minds aren’t able to correlate the secrets of the universe, there are a great many questions that go unanswered, and people go insane in their pursuit of forbidden knowledge.

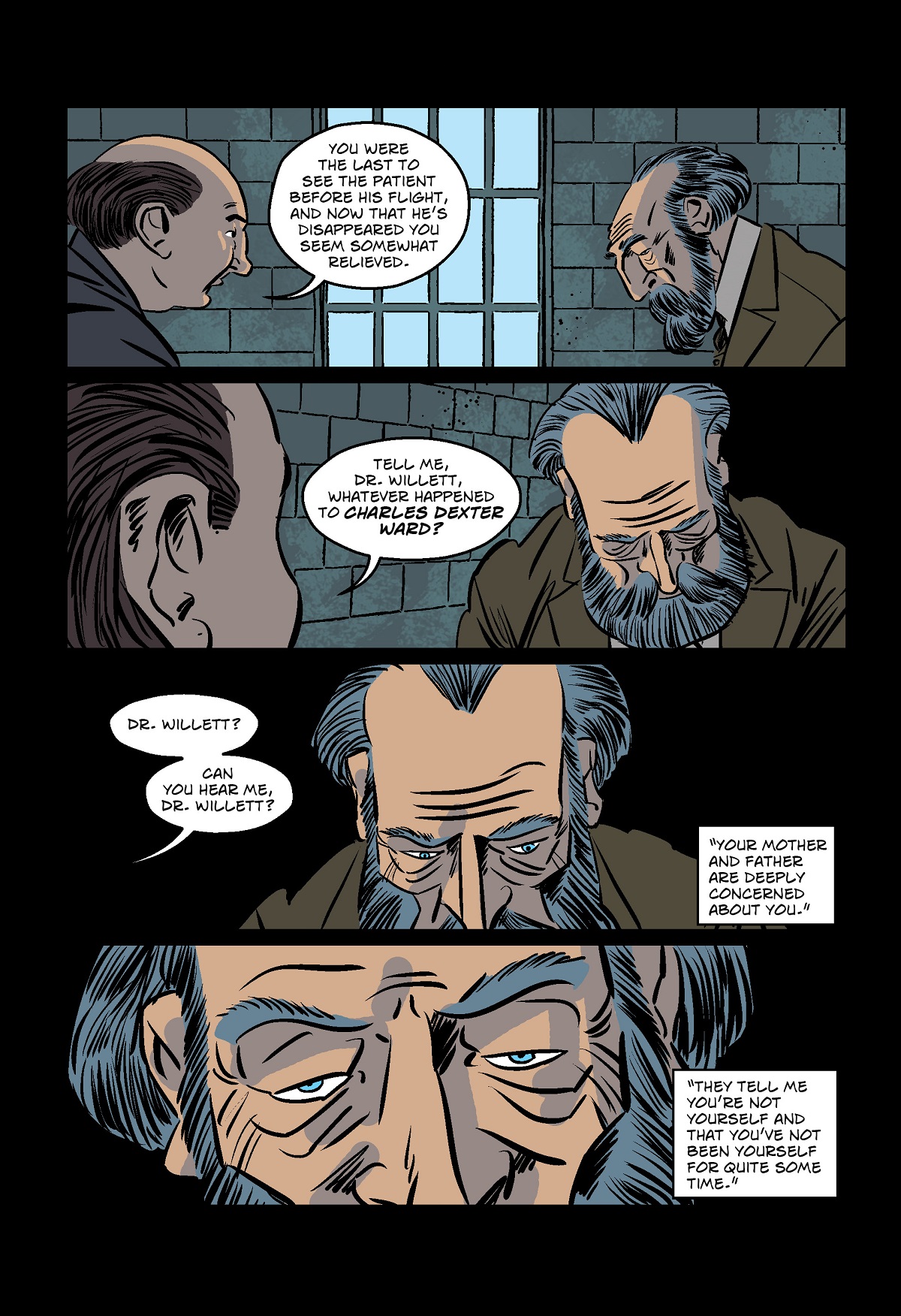

With The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, Lovecraft brings the cosmic right down to a very human and intimate level. The story begins with something as horrifyingly simple as a change of behavior, a change of personality. And that change of personality is just scratching the surface of much bigger horrors.

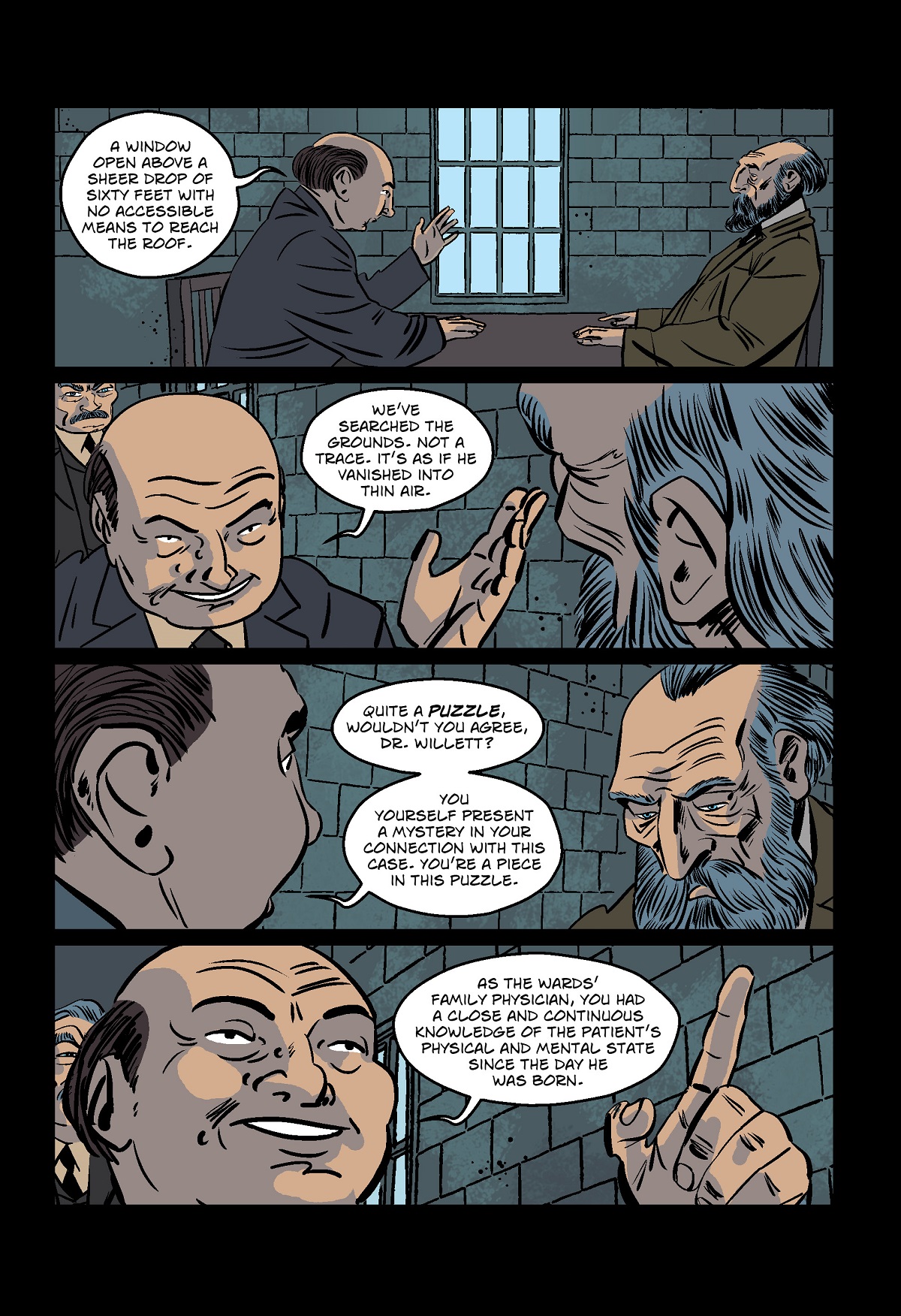

Charles Dexter Ward, investigating his family tree, uncovers a secret. And just by scratching at the surface, he becomes obsessed with the dark and hideous past of his long-forgotten and thoroughly evil ancestor, Joseph Curwen. His research begins to have an effect on him, and, bit by bit, it takes hold of him. His father, Theodore, sees a change in the young Charles and calls in the family physician, Dr. Willett, to assess whether Charles has, as a consequence of his studies, lost his mind. The story focuses on Willett’s investigation and what it uncovers.

|

| Click image to see a bigger version |

|

| Click image to see a bigger version |

Willett is our guide through the story. It is his recollection of events that holds the narrative together. I felt that with Willett being the family physician, he had just the right objective distance but was also personally invested in Charles’s well-being enough for us to see some emotion play through. Here we are able to see that what Willett knows about the boy has taken its toll, even on him. Willett is a piece of the puzzle. The book itself was also very much a puzzle, one that, as an adapter, I was going to have to take apart and put back together again.

When I adapt books I read only that book and any material relating to that book, such as essays and letters, just to get a better sense of the author’s intentions. I also get an audio reading of the book, if I can, and listen to it when I am drawing and when I go to bed at night, just to drill the story in. So by the time I come to write my version, I have not only read it several times but have also listened to it. And I say my version because an adaptation, in many ways, is a second draft, but it should also be its own thing.

With any adaptation, it is fundamentally important for you to stay true not only to the spirit of the work you are adapting, but also to the medium you are adapting it to, and every choice you make is informed by the latter. There is a good deal that is inevitably lost (because taking the text verbatim is really not an adaptation, it is a transcription, and you might as well have not bothered), but there should be equally a great deal gained through the use of visual exposition and characterization. It has to function as a body of work in its own right. A graphic novel is a graphic novel. It is not the Cliff Notes of the original work. It should have its own merits as a “work.”

Now, the first thing I do is write a detailed synopsis, something that can be pulled apart into scenes and examined. I like to have an overview, something that shows me the shape of the thing. With The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, I was dealing with a mystery, a story that calls into question when something happened as much as how, to whom, and why it happened. So it did become very much like a criminal investigation. In its deconstructed form, I would then build scenes, and, piece by piece, I would put the puzzle back together again.

|

| Click image to see a bigger version |

|

| Click image to see a bigger version |

Lovecraft often wrote about monsters, curious creatures from the stars who were here long before man. But with The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, the monsters were not simply the aberrations described as being “not wholly allied to any creature.” The real monster in this book is a man—Joseph Curwen.

What I really wanted to capture was the effect this evil, this horror, had on other characters in the book, because this is the horror we can all relate to—the mundane, the reality, the truth. It is written on people’s faces. So, often I would look to a character’s reaction to reflect that horror, rather than show the horror they were seeing.

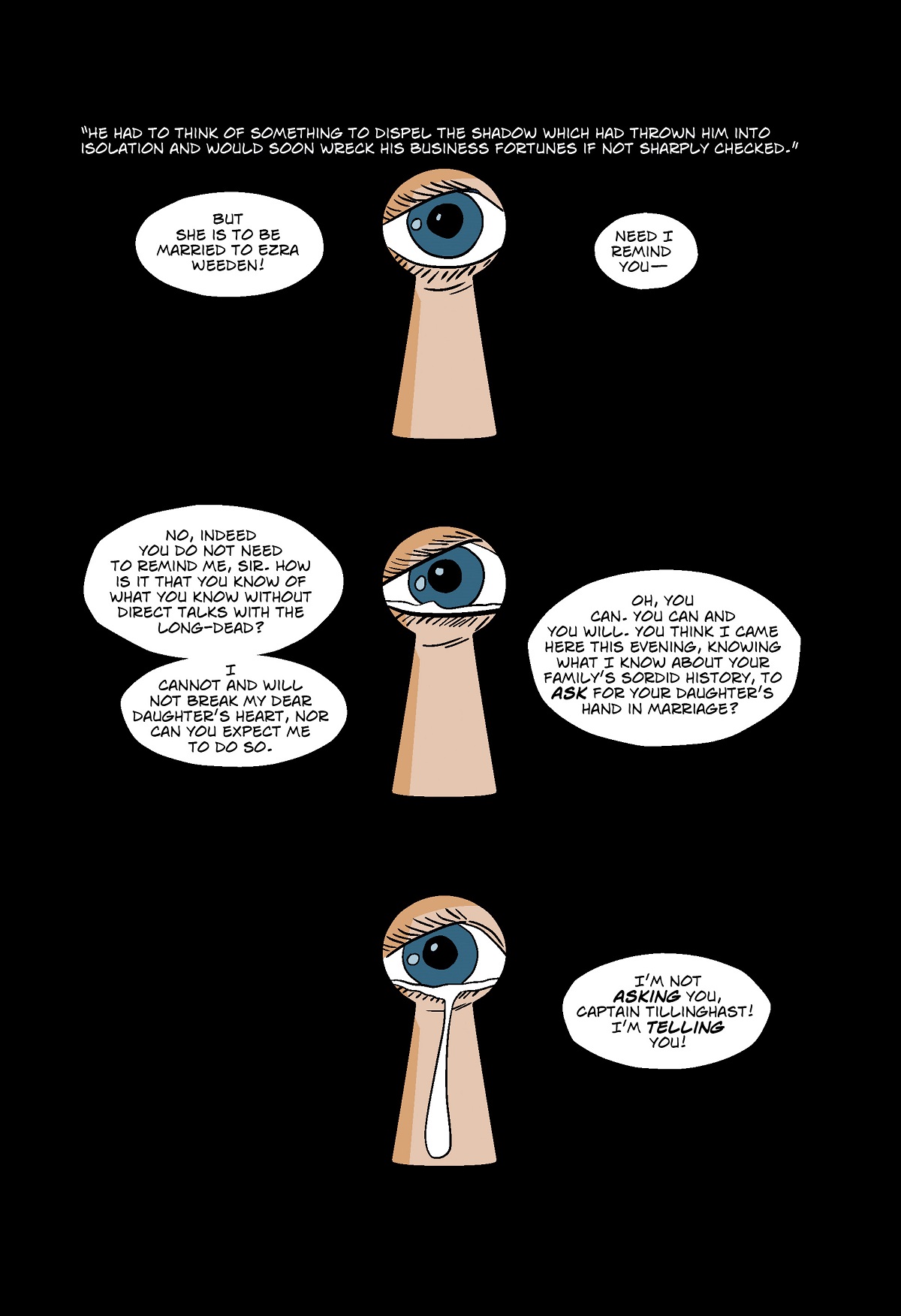

The dialogue in Lovecraft’s writing is sparse, and so I would mine much of the text for things that could make up a scene or an exchange, using it to convey the spirit of the text and to really take the opportunity to hammer home just what a nasty piece of work Curwen was. Here we see an eye peeking through a keyhole, someone overhearing a conversation. We learn that Curwen runs the town and does so by bribing officials and men of authority. How he comes by his information I will leave for the reader to discover, but mark my words, it is by unconventional means. I had originally planned out the scene in reverse, showing the view through the keyhole. I had even gotten as far as drawing it, but decided to opt for a much simpler image, one that I felt gave a significantly more dramatic pay off as the eye began to tear—it is this emotion that we can all relate to.

|

| Click image to see a bigger version |

With regard to the style and the color, the palette I use for the everyday stuff is a regular one. It is really when we see elements of the “otherworldly” that things change and I use a green tone on everything. I am showing this scene here because it is a moment when Willett is intoxicated by fumes coming from Charles Dexter Ward’s room, and Great Cthulhu makes a cameo in the form of a ruined statue on a distant world.