In his striking and soulful debut, Sentence: Ten Years and a Thousand Books in Prison, Daniel Genis revisits his stint in New York State prisons after committing a string of knife-point street robberies to fund his heroin habit at the age of 25, when he was also working at a Manhattan literary agency. His gritty picaresque features jail-yard fights; witnessings of attempted murders and suicides; routine humiliations; squalid conjugal visits with his wife; and much Kafkaesque absurdity (he was sent to solitary for purchasing other inmates’ “souls” with cups of coffee, which violated rules against commercial transactions). To counteract boredom and despair, Genis had his reading list, which included Sartre’s No Exit—a schizophrenic cellmate brought home the play’s declaration that hell is other people—and Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, which taught him that memory was the antidote to the inevitability of losing time. By turns harrowing and mordantly funny, Genis’s account illuminates how the written word helps humanity endure in the stoniest soil.

Would you like to visit the joint without being convicted? Check out what it’s like “Inside” while retaining the right to leave? Maybe sample incarceration across a few cultures and continents, various times and places? Well then, I have the travel package for you! Speaking as an ex-con who spent the years 2003 to 2014 in the prisons of New York state, I’ll be happy to book your tour from the czar’s dens of exile 200 years ago, to the mid-20th-century nightmares of Nazi-occupied Europe, to the hoosegows of today! And you don’t even need to commit five counts of armed robbery in the service of a heroin habit like I did to earn my sentence of “12 flat,” which is 10 years and three months with good behavior. All you need to do is read these 11 standout books about prison—which could easily have been twice as long—and you will have a good idea of the nature of incarceration. Be warned: It ain’t pretty.

1. The House of the Dead by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

This autobiographical novel published in 1862 describes the “life” of Russian convicts in a Siberian prison camp. The author of Crime & Punishment, a classic of moral relativism, served four years for his involvement in a politically liberal movement. His exile began after a “mock execution” followed by a commutation from the czar.

The novel describes the brutality of the guards, their wards, the civilian staff, and their commanders, basically positing that the very condition of incarceration brutalizes the human soul. Despite the setting being on the other side of the earth and the era being before the U.S. Civil War, I found the similarities between what I saw every day and what I read about to be shocking. I had an almost psychedelic moment when I read about an entrepreneurial Siberian convict carving a chess set to sell to the novel’s “gentleman” convict hero while the lifer in the cell next to mine was using spittle to make paper mâché chess pieces to sell to me. The more things change...

2. Les Misérables by Victor Hugo

Also published in 1862, this giant of 19th-century novels employs Jean Valjean as its hero, an ex-con who served 19 years in the Bagne of Toulon for stealing a loaf of bread (he actually gets 5 for the carbs; the other 14 years are for all the escape attempts). This is a very poor characterization of prison inmates in my experience. I met not one prisoner who committed his crimes because of poverty, and while I cannot say for sure who was over-sentenced, since almost every prisoner I met except for myself was not in prison for the first time, it seems that second chances are available in our society. I’m on my third, at least.

The story of Jean Valjean is best at helping one understand incarceration when it is the story of #24601. The struggle I felt to remain Daniel Genis and not become #04A3328, the 3,328th prisoner to be registered at Downstate CF in the year 2004, was a very real one. Your identity is removed in every way, from your clothing, substituted with a uniform, to your hair, replaced by a shaven pate, to your very name, erased by a number. That is why prisoners tattoo themselves so much; an identity that can only be removed with a laser is a hurdle the guards cannot (yet) overcome. By the way, #24601 was chosen by Hugo because that date in the year 1801 is when the writer believed he had been conceived!

3. One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich and 4. The Gulag Archipelago by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Perhaps the grandaddy of all writing about “the Zone,” as it’s called in Russian, these works tell you just how great you have it anywhere else but Stalin’s Gulag. Solzhenitsyn wrote his classics after an eight-year stay of his own, which he barely survived. He was saved from labor, cold, and starvation when the authorities realized he could be used in the “Sharashka,” where captive scientists worked for the USSR, a tale further told in his book The First Circle.

One Day in the Life is a short and grasping introduction to sub-zero days spent working to bring down lumber while not allowed the use of a saw. It describes the hunger that leads men to cannibalism and suicide, and the injustice and caprice with which bad things happen to good men while the bad ones are rewarded. Reading the three volumes of The Gulag Archipelago is a bit like serving out a sentence yourself; the grim bleakness that stretches for thousands of murderous pages (with photographs!) is an experience that will never allow you to feel sorry for yourself again. And remember, to share this behemoth among the samizdat circle, dedicated typists would reproduce copies through entire nights of fevered work, when a neighbor’s phone call could result in their own sentence.

5. Papillon by Henri Charrière

This story of a French convicted murderer with a charming butterfly tattooed on his chest and a stainless steel plan d’evasion containing a diamond, a roll of francs, and a razor hidden in his rectum, made for a great film that I only saw years after reading the book in prison. Devil’s Island, where Capt. Alfred Dreyfus was held a generation before Papillon, was meant to be an escape-proof little hell-island off the northern coast of South America, but our hero just couldn’t be discouraged from trying.

In Charrière’s somewhat novelized memoir of life in this tropical inferno and his many escape attempts, we get a feel for the variety of men that wind up in such places, as well as those who work there. The descriptions of solitary confinement—where our protagonist spent years being attacked by huge biting centipedes and starved after his buddy the forger was caught sending him coconuts—is eye-opening. After reading about how skeletal prisoners were no longer able to walk after a multiyear stay in solitary, it is hard to reconcile with the obesity problem among America’s inmates.

6. In the Belly of the Beast by Jack Henry Abbott

This autobiography impressed Norman Mailer enough that he got the author, a convicted murderer, paroled (this was possible 40 years ago) as a literary genius, only for Abbot to murder the waiter at his celebratory dinner. (After all, the man had looked at him funny.)

A friend of mine lived in the cell in which Abbot hanged himself 20 years later, having squandered his bizarre opportunity for redemption. This friend had little interest in Abbot, as his book is despised by most modern prisoners. It describes the inmates of Maximum Security in N.Y. state about two generations ago, when having sex with “kids,” juvenile first-time convicts, was considered okay and even manly. It is no longer seen this way, and the impression which Belly of the Beast makes is one today’s prisoners cannot abide. I mostly didn’t like the last third of the book, which was all about the wonders of Marxism, but apparently Norman Mailer had different standards. This one is definitely a period piece, but the poor waiter’s end did not hurt its reputation.

7. Newjack by Ted Conover

A work of undercover reporting! Conover went through the Correctional Officer’s Academy in Albany in order to get a job at Sing Sing, where all of New York’s old-time gangsters used to take a seat in “Old Sparky,” the electric chair. Reading this memoir gives you a good look at the other side, the life of a prison guard. We don’t hear from this contingent too much, and it’s not a popular field. I think you’re better off telling someone you met in a bar that you are an ex-con or an escaped one than a C.O. Nevertheless, these men are doing a very hard job that can have lethal consequences, and we should not judge them all by the characterization we get from the screen. Like me, Conover met his share of sadists and guys just doing a job. The book is a bit skewed because the author really wanted to see the best in the prisoners, his wards, and I commend him for his Christmas kindnesses… I wish I had seen more of that over my 10 years in, but then again, Conover himself may have worn the uniform but wasn’t a real C.O.

By the way, you have to read this one in County. Upstate it’s censored. Not because of the dastardly truths the author reveals, but because he describes the Sing Sing locker room.

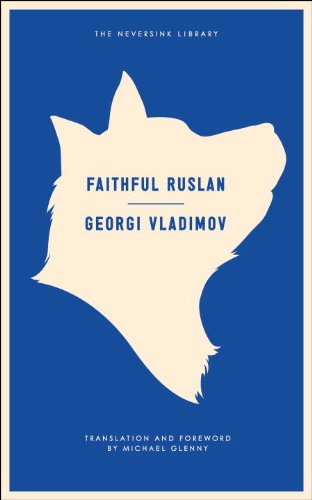

8. Faithful Ruslan by Georgi Vladimov

This more obscure Russian novel from 1975 also tells the story of a camp guard, only a canine one. Of course, it’s all a metaphor, and of course it must be read in the context of the Soviet Union, where millions of people were kept in prison. Ruslan is an abandoned camp dog, and the novel is the sad story of a character made obsolete. His end is a tearjerker… except that he spent his life wishing to bite into the completely innocent, cowering, and helpless prisoners he knew to despise, but not why. It’s a talented author who draws a tear for such a character!

I read Ruslan to better understand my overseers, when they were cruel or sharp with me, and to give them a human face. Of course, Ruslan was a dog. But he was a very Soviet dog and if you’ve also read The Heart of a Dog by Bulgakov, it’s a good pairing.

9. Shantaram by Gregory David Roberts

A wonderfully interesting tale of crime and punishment in India. Prison in the subcontinent is rough; you’ll have little to complain about once you read about the general acceptance of transparent worms in all available water. The drug abuse that led the author to his fate is a good meditation on the dangers of that path, if all the other “usual suspects” aren’t enough.

Shantaram is 1,000 pages of “Locked up Abroad”; it will terrify you and then mortify you, finally leaving you very grateful for your comfortable cot in a First World facility. Men in N.Y. state prison wouldn’t eat bread that had fallen on the floor; in poorer nations you cannot even count on food without payment. This novel is colorful and exciting and autobiographical without being too much so.

10. Survival in Auschwitz by Primo Levi

Also called If This Is a Man, this is a dark piece of writing about going from a happy life as a member of an intellectual Jewish family in Italy to living moments away from death in the Nazi extermination camp of Auschwitz. It’s harsh, especially since the narrator knows all of the Jews herded to their deaths or forced labor. He remembers them as Rabbis and professors and doctors and gangsters… only here they are stealing spoons of sugar solution meant for nursing Aryan mothers and being mercilessly killed the moment they are viewed as no longer fit for work.

When the narrator witnesses his father perish, and wails at his absolute inability to help him in any way, it is soul-shaking. I was completely ashamed of every time I had called our guards ‘”Nazis” or complained about the food Inside. After all, just like in the Soviet Gulag, these people were innocent of any crime.

Primo Levi eventually committed suicide, as did so many others who made it through the camps. Perhaps it was the guilt of surviving that was so unbearable. I know that I still feel bad about all the people I remember inside who will never be leaving like I did. They committed more serious crimes than me, but they didn’t seem all that different.

11. A Man in Full by Tom Wolfe

This 1998 novel only has about 120 pages set inside prison, but boy are they on point! I would have loved to have asked Tom Wolfe how he knew? How did he get the sights and sounds so right, and most of all the fear? Prison wears away at your soul and takes years off your life by keeping you in an unnatural state, afraid from the moment you get up until the cell door closes, and even then the fear follows you into your nightmares. In this novel, the hero is terrified of being raped and just when it looks like there can be no reprieve, Tom Wolfe allows such a deus ex machina that its very placement is tongue in cheek. An earthquake brings down the prison walls and allows our protagonist to escape his fate in all senses. Never have the walls of Jericho fallen with such good timing.

This is a very good novel to read about prison because it also deals heavily with Epictetus and the Stoic philosophy. This is what allows a man to suffer, especially when things are not going to get better, maybe not for a while, maybe never. I knew that situation well, and somehow, despite being a literary celebrity, so did Tom Wolfe!

Bonus: Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban by J. K. Rowling

I don’t mean that this particular volume of the Harry Potter septet has any special significance to incarceration. It’s just emblematic of all the escapist reading prisoners like me do to get through their limited lives. I actually did read all of Rowling, even if it was through clenched teeth towards the end, and the amount of science fiction and Cold War espionage I read as dessert after Heidegger is embarrassing. Prisoners don’t necessarily want to read more about prison, although the books listed above—plus those that didn’t make the cut—help one to understand the condition of incarceration. But if you ever find yourself in a real prison, leave room for the books that take you away from the walls and bars that define your life already!