I can easily see why poets took to Twitter,” says poet Eduardo C. Corral, whose Yale Younger Poets Prize–winning Slow Lightning was a hit in 2012 and whose second book, Guillotine, is forthcoming from Graywolf in 2020. He maintains an active presence on the platform, which he says mimics the ways poets think: “Click, click, link, link—that’s something we’re always doing in our heads, too, with words. We’re clicking on them to see where they take us, the different pathways. I think poets intuitively know that the first hyperlink was a word itself.”

With a generation of digital natives coming of age as readers and writers, the stereotype of a brooding teen clutching a worn copy of Ginsberg is being replaced by one of a teen using “Holy! Holy! Holy!” as a bio line on Instagram or tweeting about an odyssey in the supermarket. Still, the debate over poetry’s future—digital or otherwise—persists; a 2015 article in the Washington Post suggested signs pointed to the demise of the form, but in 2018, the Atlantic assured us that “far from ‘going extinct,’ as it was once predicted, poems are viral, vital—and invincible.”

The curious influx of how-to guides to reading poems, some with glib titles acknowledging the form’s contentious place in literary life (among them, 2016’s The Hatred of Poetry by Ben Lerner and Don’t Read Poetry, due in May from Stephanie Burt, who is interviewed on p. 31), appear less a symptom of poetry’s uncertain future than a side effect of its having a larger readership than ever. Indeed, the National Endowment for the Arts reported a substantial increase in the portion of U.S. adults who read poetry, from 6.7% in 2012 to 11.7% in 2017; in 2017, there were an estimated 28 million poetry readers.

Social media is at the center of poetry’s “viral vitality.” Though Twitter revolutionized the distribution of tiny texts, other platforms used to share visual and written content, such as Instagram and Tumblr, have spurred the development of new ways of transmitting and consuming digital writing. A glance at the common poetry hashtags on Instagram—#Poetry, #WritersOfInstagram, or the edgier #WordPorn—suggests an audience ready to identify, share, and interact with fellow readers and writers. That these labels often appear alongside their desired outcomes—#Inspire, #Succeed, #PoetryIsNotDead—suggests the wish-fulfilling power of placing work online.

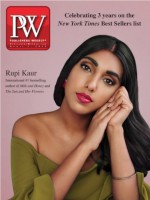

Finding readers of poetry in the flesh (and getting them to purchase books by poets in airports or bookstores) has historically been challenging, but a growing number of digital poets—among them Atticus, Rupi Kaur, and R.H. Sin—have nurtured and developed their readerships through digital platforms, drawing the attention and endorsement of major publishers and celebrities alike. These poets have been described as managing a symbiotic relationship between the writing and its audience, which translates to a kind of ready-made marketing strategy for publishers and booksellers.

Connection, Community, and Controversy

Kaur, whom the Atlantic dubbed a “poet-entrepreneur” and whose book Milk & Honey sold more than 3.5 million copies, got her start as a performance poet, opening her Instagram account in 2013 after a breakup. She gained a small following posting poems and artwork and has watched the exponential growth of her readership over the past few years; she now boasts more than 3.6 million followers.

“I have strong connections with the women in my community and neighborhood,” says Kaur, who lives in Toronto. “Suddenly, I was having those same connections globally. Women were responding to these pieces. Some of the women are now my close friends. Their responses were ‘Whoa, I’m not alone.’ ”

In her own poetic practice, Kaur says, she emphasizes the importance of separating “the art from the business,” remaining conscientious about the platform’s role (and her millions of followers) in shaping her writing. “Over the years, I’ve distanced myself from it,” she notes. “I realize that when I had fewer people watching, I was more raw and vocal. When the numbers started to grow, I started to overthink things. I felt more pressure to be correct and perfect all the time.”

“As soon as you’re on social media, you’re branding yourself,” says Paisley Rekdal, Utah’s poet laureate, whose sixth collection, Nightingale, is coming out in May from Copper Canyon Press. “Every day, I’m trying to ask myself what kind of person I’m trying to be on social media, because I know that person isn’t really me—what kind of role model for my students, what kind of political citizen, what kind of literary citizen—while at the same time recognizing that I’m selling my work as poet laureate, or as university professor, or as writer Paisley Rekdal. All of these are things that I’m promoting, so somewhere down there is me.”

Poet Danez Smith, who uses the pronoun they, is the author of Don’t Call Us Dead and has more than 35,000 followers on Twitter. They say they don’t see the platform as serving a critical function in their identity as a writer. Nevertheless, they cite social media as having a positive effect on their practice. “It’s maybe made me more comfortable in things that I was already doing in my work, in reaching people through a language that is common and colloquial, and finding the lyric within how we talk to each other when we’re not trying to be poets; realizing there is a poetics within that as well. Social media lets people see that the poets they like are just real people who have regular thoughts and are also politically engaged and can think about more things than a line break. It’s a way to engage with poetry where you don’t need any type of academic or educational privilege. And if people can see their favorite poets just being casual fans of poetry, then maybe poetry can also be for them.”

Social media’s ability to casually connect audiences with similar interests, or to mobilize entire communities, is perhaps its most powerful attribute. Rekdal says that in the past, she has used Facebook and Twitter for a range of written projects. “I’ve asked questions for translation help, and I’ve gotten it. There was research I did on my nonfiction book The Broken Country that I would not have been able to do without putting out a call and getting names from people in the community. There are things I couldn’t have done as a writer, or that would have taken more time, without social media.” Rekdal is currently drawing on digital networks to organize an all-Utah poetry festival.

Poet Rachel McKibbens, author of Blud, who co-owns a restaurant and runs a successful poetry series in Upstate New York, argues that social media has been central to finding and maintaining her community. She called on this community in December, drawing attention to poet Ailey O’Toole’s widespread plagiarism of lines from McKibbens and other poets, which turned into a poetry scandal that made headlines. The resulting Twitter storm prompted the cancelation of O’Toole’s forthcoming book.

“I did not expect that post to grow as fast as it did,” McKibbens says. “I didn’t really understand the extent of the plagiarism at that point. It wasn’t until the other Twitter members joined in the fray and started closely examining not just the poetry but interviews. What hurt the most about the plagiarism is that the choice of lines taken were very lived, very survived experiences. It leveled me in a way I was unprepared for, and it kept growing as the days progressed.”

The ease of digital poetry consumption—and the widespread recirculation of fragments and lines on Twitter—is one of the platform’s chief draws and one of its most potentially problematic features. Once a line is removed from its original context, it is open to misreading or even misattribution, as poet Marty McConnell, a friend of McKibbens, knows. “Marty learned the hard way by writing a poem called ‘Frida Kahlo to Marty McConnell,’ a poem that is now attributed to Frida Kahlo,” McKibbens says.

“One of the books I recommend my students read is So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed, about what happens to you after a media takedown,” Rekdal says. “I read a tweet one time, and I thought that it was a perfect summation of Twitter: ‘Twitter is like playing tag, and every day, you just pray to God you’re not it.’ ”

Echo (and Narcissus) Chambers

But despite social media’s seemingly endless array of channels for discourse on poetry, and the countless shapes such discourse can take, some poets wonder whether social media may be limiting—whether, due to algorithms or their own narrow tastes, they may be responsible for creating poetic echo chambers on the web.

“What I fight against myself, personally, is, does it become groupthink?” Corral asks. “Does it become that we’re all sharing the same kinds of poets and aesthetics and links? One of my teachers, Alberto Ríos, says, ‘The task of poet is, when there’s a loud noise over there, to turn and look away from the noise.’ ”

“You’d think that there’d be an infinite number of links, an infinite number of conversations going on,” Rekdal says. “And yet, in a weird way, it still feels like there are five or six books that we end up talking about—five or six topics. I’m not sure if that’s the algorithm speaking or not. Shouldn’t this be a bigger conversation, just because of the sheer number of voices? Why are we still having only the same conversation?”

What McKibbens describes as “top-40 easy-listening poetry” is an aesthetic narrowing that poets and readers of poetry might not even be aware of.

“Pieces can go viral, which is great, but that doesn’t represent the true breadth of what poetry is and can do, largely because of the format in which we read certain types of work and not others,” Rekdal says. “This is not to say that the poems that work online are terrible. It just means that [social media] slowly but surely changes the way in which we imagine a successful aesthetic to work. It can have a kind of effect on our very syntax. And I don’t think we really fully appreciate that.”

Byte-Size Ballads

Just how differently readers process whole poems (or endless fragments) digitally versus on the physical page remains another unanswered question about poetry on social media. “I wonder how engaging with so many microbits of language every day affects us,” Smith says. “How much reading time or brain space I’m putting in. If I’m on Twitter for an hour, sometimes I look up and think, ‘Okay, how many words did I read and how many pages of a book does that add up to?’ I think it is good practice to pull yourself away from it and really consider how much time you’re spending living in a digital space when there is so much in the living, tangible, walking, waking world.”

But, Rekdal notes, “there’s no going back. Everyone has to live with it at some level, even if you’re the writer who decides you’re never going to be on these social media platforms. There are certain types of work we wouldn’t have been able to have without the printing press, so there are many things that social media is going to change and amplify.”

Kaur posits that criticism of social media’s influence on poetry may have more to do with resistance to democratizing a form that wasn’t always democratic or accessible to all. “It’s similar to how, for a time, people only read hardcover books, and mass paperback was created for those who couldn’t afford them,” she says. “Social media has married poetry to a nontraditional platform.”

“I’ve read every essay, every critique that this is all throwaway poetry, or that it’s the death of poetry,” McKibbens says. “But they’ve been saying that of anything that makes a form popular. Poetry and storytelling didn’t begin with Byron, I promise.”

Maya C. Popa is a poet and PW’s Poetry Reviews Editor.

Volume 266

Issue 13

04/01/2019

Volume 266

Issue 13

04/01/2019