In recent years, a growing number of children’s publishers have begun to develop their own proprietary content, often prompted by an unmet need in the marketplace and the desire to fill that need quickly. The publishers control the rights, so if the new IP strikes a chord, they can bring it into new formats, entertainment platforms, and licensed products.

“If there is demand for a subject and not much is coming in from our agents and authors, we’ll develop it ourselves,” says Valerie Garfield, v-p and publisher of licensed and novelty publishing at Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing. “We can identify a need and get to market quickly, and that’s a big advantage.”

Garfield’s team will have created 31 original series, including 14 middle grade and 17 chapter book series, by the end of 2020, with four more in development for 2021 and beyond. The first three were the middle grade series Cupcake Diaries, You’re Invited to a Creepover, and Cheer!, all introduced in 2011, followed by two chapter book series, Heidi Heckelbeck and Captain Awesome, in 2012. Both Cupcake Diaries and Heidi Heckelbeck have exceeded one million copies in print.

“We realized that part of the appeal of series we loved growing up, like the Baby-Sitters Club, was that they came out at a pace where if you loved them you could keep reading until the end of time,” Garfield says. “We want to feed these kids’ interests.”

To this end, S&S commits to six books per year for any of its original series, with some complete after the first six and others continuing. Cupcake Diaries, for example, is on book 33 and counting.

Speaking of the Baby-Sitters Club, Scholastic’s trade division has been publishing original IP since then-publisher Jean Feiwel came up with the idea for Ann M. Martin’s series, which began in 1986. “If one of my colleagues in the school channel says that we need more middle grade horror, we can jump on it, come up with an idea, find an author, shape it the way we know it will appeal the most to young readers, and then sell half a million copies in less than a year, which is what we did with K.R. Alexander’s The Collector,” says David Levithan, editorial director at Scholastic’s trade division. “I’ve never really thought of it as IP. It’s just ‘brainstorming ideas for authors,’ and it’s pretty much a part of the DNA here at Scholastic.”

Almost 20 years ago, the company formed a weekly “idea group,” and “well over 100 books and series have started in that room,” Levithan says.

Creating a franchise

Since its founding in 2015, Macmillan Children’s Publishing Group’s Imprint has had a mission to develop IP, along with acquiring author-driven and licensed titles. Its first IP and one of its first projects overall was the chapter book series Super Happy Party Bears, which is now being considered for extensions into animation and merchandise. Other projects since then have included chapter book series, such as Wild Child and Prince Not-So Charming, YA novels including Shadow State and Solstice, and most recently a series of board books, Mind Body Baby.

“If we’re going to do this, we should at least feel like there’s a possibility that it could become something else since we’re spending so much time on it,” says Erin Stein, founder and publisher of Imprint. “But it’s not like we’re not going to do it if it can’t be licensed. Publishing is still the core.”

Many of Simon & Schuster’s properties have been optioned for TV, and one is in active development with a major broadcaster. “Even if a series is only six books, there’s a pretty extensive world, so the next generation is to recreate that world in new formats,” Garfield says. “But if you’re thinking mainly about TV or film, that’s working at cross-purposes. Most of our series have potential for TV, but the purpose is to create a world so kids can read about it.”

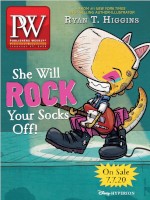

Levithan agrees, saying, “We’re in the book business, so [our original ideas are] always meant to be great books, first and foremost. But luckily, great books can often be turned into franchises in other formats.” One example is Upside-Down Magic, a series by Emily Jenkins, Sarah Mlynowski, and Lauren Myracle, which will be a Disney Channel movie this summer.

“We live in a world where content is currency,” says Claudia Gabel, editorial director at HarperCollins Children’s Books. “The central goal of our IP program is to deliver high quality and commercially appealing storytelling that can thrive in a variety of different sales channels and mediums. Not every book, whether it’s a standalone or part of a series, is going to evolve beyond that. But as IP content creators, we have to keep up with how and where our young audience is consuming and engaging with media, which means thinking of each IP project as a potential springboard to another platform.” One example is Harper’s Dead Girls Detective Agency series, which is now a Snapchat original TV show.

Harper has been creating IP for many years and launched a focused program 10 years ago; it has created close to 100 original properties since then. It has a team of editors who specialize in original IP, although they also acquire titles traditionally. The company hired Annabelle Saks in November 2019 as director of media, a new role; she is charged with helping leverage Harper’s IP across all forms of media and participating in the ideation and editorial processes.

The importance of the author

Though original IP is planned and maintained in-house, outside authors are typically brought in when it is time to begin writing. “HarperCollins has a strong legacy of finding new talent and amplifying new voices, and that philosophy is what drives our IP strategy,” Gabel says. “We may have great ideas for books, but as always, the perfect writer is the X factor in all of our successes.”

Stein says, “There is still a lot of creative license and input for the creators. We can work with first-time creators on something like this and then they can go on to do other projects with us or use it as a springboard to get jobs with others. It’s a nice way to work with new talent.”

Simon & Schuster’s Pulse imprint for teens has created a number of original IP projects, several of which are being actively pitched for film and television. “The author adds a whole other layer to it,” says Mara Anastas, v-p and publisher, Simon Pulse and Aladdin. “It’s an opportunity for a really good writer who’s struggling to come up with a good idea or is figuring out what’s next.”

Even though authors do not retain rights, IP projects benefit them in terms of publicity and earnings, Anastas adds. When Dimple Met Rishi author Sandhya Menon, for example, is frequently requested for speaking engagements, where she draws crowds of teens. Simon & Schuster sold film rights, licensed the novel into six territories, and ended up giving the author a seven-book deal.

“This is not about excluding authors,” Garfield emphasizes. “The point is to be able to add publishing we don’t see being tackled, or that we need to produce at a pace one human can’t produce.”

Rejuvenating the classics

Several publishers are refreshing properties they already own by developing original content. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt has reimagined its retro educational gaming properties Carmen Sandiego and the Oregon Trail, which came to HMH through the merger of Houghton Mifflin and Riverdeep in 2006. “We always want to make sure we think about the long-term resonance of a property,” says Mary Wilcox, v-p and associate publisher of HMH Books for Young Readers, noting that new and reimagined IP helps extend the longevity of classic brands.

HMH has published Choose Your Own Caper adventures and graphic novels for Carmen Sandiego, starting last January in conjunction with the debut of Carmen Sandiego on Netflix. In September, it will publish its eighth title, an original middle grade novel by Emma Otheguy, Secrets of the Silver Lion. The Oregon Trail has inspired choose-your-own books, as well as a gift title for nostalgic adults called ...And Then You Die of Dysentery: Lessons in Adulting from the Oregon Trail.

Introducing a property to new audiences is often one of the goals of developing original content. For Nancy Drew—which Simon & Schuster has owned, along with the Hardy Boys and Tom Swift, since its purchase of the Stratemeyer Syndicate in 1984—“we’re bandying about the idea of a picture book,” Anastas says. Aging the property up is also a possibility.

Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys are refreshed every seven years or so with new covers and updated text, and they have been supported by new storytelling such as in-house-produced chapter books, licensed comic books with Papercutz and then Dynamite, and tie-ins to TV and film spin-offs, including a series currently on the CW network. Tom Swift Inventors Academy, meanwhile, debuted last summer as the latest publishing reboot of that classic.

Disney Book Group has been reimagining its brands through all-new stories as well. Past successes have included Serena Valentino’s The Beast Within and Poor Unfortunate Souls, and Jennifer Donnelly’s Lost in a Book, all inspired by Disney princesses.

Titles in 2020 and 2021 will include the Mouse Watch, a middle grade series by Walter Pepper, featuring Gadget Hackwrench of Chip ’n Dale; the Queen’s Council, a Disney Princess–rooted historical fantasy series by authors such as Emma Theriault and Livia Blackburne; Meant to Be, a four-book upper-YA series inserting the princesses into modern romantic comedies, written by Julie Murphy, Jasmine Guillory, and others; and City of Villains, a three-book crime-procedural series by Estelle Laure, featuring characters such as Maleficent and Jafar.

Similarly, DC Books for Young Readers recently debuted an IP initiative encompassing middle grade and YA novels featuring new characters and plots that are separate from the DC Universe of superheroes, although they take place in the same world. The first three titles are Anti/Hero, written by Kate Karyus Quinn and Demitria Lunetta and illustrated by Maca Gil; My Video Game Ate My Homework, written and illustrated by Dustin Hansen; and Primer, written by Thomas Krajewski and Jennifer Muro, all set for 2020. These middle grade stories will be followed by two YA titles in 2021.

Spearheading partner content

Publishers also take the lead on new content development in collaboration with licensors or author estates, although they do not typically share in ownership. Such original content drives sales. “Kids today don’t want to read an adaptation or novelization of an episode,” says Debra Dorfman, Scholastic’s v-p and publisher, global licensing, media, and brands. “They want the untold story or a spin-off story. With all of our licensors, that’s the first thing we ask, whether they will let us develop something new.” Among Scholastic’s recent originals tied to licenses are novels for Archie Horror, Katy Keene, and Riverdale, all with Archie Comics.

Scholastic’s licensed and novelty publishing team has also developed original IP in the form of a meme book titled Grumpy Unicorn: Why Me?, released this past September. “We do a whole bunch of meme books and they do very well in [Scholastic’s book] fairs,” Dorfman says. Thanks to strong sales in the trade and especially school markets, the goal is to extend the Grumpy Unicorn property. “We loved the character so much we spun it into a young graphic novel, and we hope to develop it further.”

Longtime Dr. Seuss publisher Random House works collaboratively with Dr. Seuss Enterprises on original content. It recently launched a series of board books featuring characters such as Cindy Lou Who, Max, Horton, and the Lorax. “We wanted to introduce characters that young kids will ‘get’ later, but in a toddler-friendly way,” says Mallory Loehr, senior v-p and publisher at Random House Books for Young Readers.

A desire for a stronger position in seasonal publishing beyond the Grinch led to a series of holiday board books, including Spooky Things, Lovey Things, and Spring Things, all featuring Thing 1 and Thing 2. A third new series consists of paper-over-board gift books for all ages, including You Are Kind, starring Horton, and I Love Pop. “We’re really coming up with formats that solve problems,” Loehr says. “And by featuring some less-well-known characters, we can help elevate the brands.”

The success of the Seuss gift books led Random House to consider opportunities for P.D. Eastman’s classic titles, resulting in the publication of You Are My Mother, set for March, and an upcoming title with a mindfulness theme, Whoa, Dog. Whoa!

Publishers also can have a strong hand in developing spin-offs for newer series. Macmillan’s Farrar, Straus and Giroux, for example, has taken the Pout-Pout Fish, which it began publishing in 2008, into new territory by collaborating on original IP. Ownership stays with the author and illustrator if they are involved; Macmillan may retain the copyright in other cases, but the underlying IP remains with the creators.

“[The original Pout-Pout Fish] hit the New York Times bestseller list without too much effort, so we knew we had something that was resonating with little kids,” says FSG executive editor Janine O’Malley. After building on the original jacketed hardcover with further titles, followed by holiday-themed board books and four beginning readers—all written by original author Deborah Diesen and all but the readers illustrated by Dan Hanna—it added FSG-produced content starting in 2018. Spin-offs include 8 x 8s, numbering eight to date with more to come, as well as novelty books and merchandise.

Several publishers report that they are developing wholly new, proprietary IP for future seasons. “The main challenge for publishers with this is that they have to make time for it,” Stein cautions. “Often they’re not hiring a dedicated staff for this. You really have to try to make it a priority to focus on it.”

Volume 267

Issue 7

02/17/2020

Volume 267

Issue 7

02/17/2020