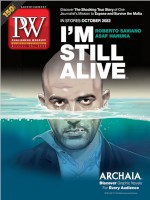

Reza Aslan looks good for a guy in quarantine. Speaking over Zoom from his Los Angeles home in late June, where he, his wife, and their children are isolating after returning from a two-week trip to Portugal and testing positive for Covid-19, Aslan is animated and gracious, more boyish than one would expect for a 50-year-old father of four.

Partly it’s the afterglow of a great trip, but Aslan is also a man on a mission, energized by his cause. “My goal is that every American remember the name Howard Baskerville,” he says, “the way that we remember the name Lafayette. Maybe I need a hit hip-hop musical to make that happen.”

Aslan’s new book, An American Martyr in Persia: The Epic Life and Tragic Death of Howard Baskerville (Norton, Oct.), may not have the chart-busting soundtrack of Hamilton, but it does feature a young man who, much like Alexander Hamilton’s friend the Marquis de Lafayette, put his life on the line for a democratic revolution in a foreign land. In the case of 24-year-old Presbyterian missionary Howard Baskerville, that distant country was Iran.

For readers who see the words “Iran” and “revolution” and picture the stern visage of the Ayatollah Khomeini and protestors overrunning the U.S. embassy in Tehran, it may come as a surprise that the 1979 uprising that brought Khomeini to power was the third of three revolutions in Iran in the 20th century. The first of those—the Persian Constitutional Revolution—was the cause that Baskerville died for in spring 1909. Begun four years earlier, it pitted students, business leaders, and religious groups against the ruling Qajar dynasty and resulted in the country’s first constitution and independent parliament. By the time Baskerville arrived in fall 1907 to teach English and preach the gospel at the American Memorial School in Tabriz, however, those gains were under grave threat from the country’s tyrannical ruler, Mohammed Ali Shah.

Aslan, who fled Iran for the U.S. with his parents and sister in 1979, grew up knowing the story of Baskerville. Schools throughout Iran were named after him, and his tomb in Tabriz was a pilgrimage site. But the 1979 revolution eventually “wiped Baskerville from the country’s collective memory,” Aslan says, and he is largely unknown in the U.S.

The story of an American Christian missionary who fought alongside his Muslim students for Iranian republicanism is well suited to Aslan, whose life and religious scholarship intertwine both faiths. Raised in a secular Muslim household, he converted to evangelical Christianity at age 15. The summer before he entered Harvard for a master’s in theological studies, however, Aslan left Christianity and returned to Islam. He also holds a PhD in the sociology of religions from UC Santa Barbara and an MFA in creative writing from the University of Iowa, and has published bestsellers about both faiths, including 2005’s No God but God: The Origins, Evolution, and Future of Islam and 2013’s Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth.

After his most recent book, 2017’s God: A Human History, Aslan went searching for a new project and found that the story of Baskerville “kept popping up.” On the one hand, he was looking to do something different: he had publicly vowed, after the publication of God, that he would never write another book about religion. (“That book almost killed me,” he says with a chuckle.) But the outlines of Baskerville’s life also struck a deep chord with Aslan. “It’s a story about a pious young man who, confronted with an intolerable situation, is activated to do something about it—to actually put his beliefs into practice,” he says. “That is the kind of story that really animates me.”

It was also a story that Aslan had told before, in Zealot. He sees numerous parallels between that book and An American Martyr in Persia, among them that there are only a few primary sources to rely on. Just two letters record Baskerville’s thoughts at the time of his death: one was written to his family but never mailed (it was found folded in his pocket after he was killed); the other was sent to the American consul general in Tabriz and explains why he decided to take up arms alongside his students.

Aslan says “everything clicked into place” when he read Baskerville’s letter to the consul general. “He was very clear-eyed about the fact that this was him preaching the gospel. This was him actually living out the words he had been spouting—to very little effect—to the students he was supposed to convert to Christianity. At a certain point he realized that not just as a Christian, but as an American, this was his duty.”

In the book, Aslan traces Baskerville’s sense of duty back to his junior year at Princeton, where he took two courses on constitutional government and international law taught by university president Woodrow Wilson. “If you go back and look at what Wilson was preaching at the time, he was quite a political radical,” Aslan says. “He was unapologetically talking about democracy being the birthright of all peoples in all parts of the world. And he’s doing it in spiritual terms. He was saying this is what the lord God wants for all humanity, and if you call yourself a Christian, your job is to go out there and—through revolution—make sure that all human beings, in all places, are free.”

Under the influence of Wilson and his own Christian piety, Baskerville came to believe, Aslan says, “that political freedom and spiritual salvation were entwined—they were one and the same for him.”

In the wake of America’s withdrawal from the Middle East, the storming the U.S. Capitol by anti-democratic protestors, and the Christian right’s successful effort to overturn Roe v. Wade, Aslan knows that a book extolling the virtues of a faith-based, democratic globalism is bound to have its fair share of detractors, but he’s ready to defend Baskerville’s viewpoint. “Nothing has changed” since 1909, he says. “People have the right to be free, to have a say in the decisions that rule their lives. That’s a right that either we all have, or it’s a right that none of us have. What Baskerville represents is what Christianity truly is—these incredible, almost otherworldly values about what it means to be human and what we owe one other.”

If Aslan seems not just ready but eager to confront his critics, it may be because he’s waded into hot water before. Zealot zoomed to the top of the bestseller charts after he tangled, on air, with Fox News correspondent Lauren Green over his authority, as a Muslim, to write a book about Jesus. In a less fortuitous episode, the second season of Aslan’s CNN show Believer was cancelled in 2017 after he called President Trump a “piece of shit” on Twitter.

“People on the right went bananas,” Aslan says of the latter incident, “but I also got a lot of anger and hatred from liberals and progressives who said, ‘It doesn’t matter who is in the office, you have to respect the office.’ And my answer was, I’m sorry, what now? What the fuck are you talking about, ‘respect the office’? Maybe it’s because I’m Iranian, and I have a different sense of the relationship between a citizen and the government, but this idea that I have to bow to an empty office, regardless of the stain that may be occupying it, is, to me, indicative of the problem. It’s the idea that maybe we can just reach across the aisle, or that the institutions are permanent. Look, I was born in a country that was one thing one day and something completely different the next day. There is no such thing as permanence. There are no pillars. The pillars are whatever we make them to be.”

Asked where he finds hope that the U.S. can once again embody the values he sees in Baskerville, Aslan points to the younger generation—20-somethings who are “looking at what we have done to the planet and to this country and realizing that all the old assumptions don’t work anymore.”

One of the old assumptions he hopes to disprove with An American Martyr in Persia is that the relationship between Iran and the U.S. can’t be based on “mutual respect.” Claiming that Iranians are “by far the most pro-American population in the Middle East,” and that they “have the ability to distinguish between Americans and the American government,” Aslan says he doesn’t think it’s “pollyannish” to believe that Baskerville can serve as a bridge between residents of both countries, “who have so much more in common than either realize.”

Or as Baskerville famously said when he was told that the Persian Constitutional Revolution wasn’t his fight: “The only difference between me and these people is the place of my birth, and that is not a big difference.”

Volume 269

Issue 34

08/15/2022

Volume 269

Issue 34

08/15/2022