In these title close-ups, authors and editors share their thoughts on creating books within the burgeoning middle grade subgenre of mythology-inspired fantasy-adventures. For more insights on this trend, see our main feature.

Amari and the Night Brothers #3

B.B. Alston (Balzer + Bray, Oct.)

Editor Kristin Rens: What drew me in when I first read it was the way in which it felt like a love letter to classic books and films like the Percy Jackson series and Men in Black, while also feeling totally new and fresh. It has all the intricate magical world-building, genuinely surprising twists, and heart that readers want in a fantasy, with the added layer that Amari’s challenges in the supernatural world very intentionally mirror those that many kids—especially children of color—face in our real world.

Alston: The premise for the Amari books is that everything we think of as myths and legends actually exists—just hidden away from the ‘known world’ we all experience in real life. So, in Amari’s world there are bits and pieces of mythologies from around the world, as well as references from pop culture, which sort of represents a modern mythology in many ways. I thought it would be really fun to see how an inner-city kid reacts when experiencing elements that are foreign to her. Amari struggles with who she is and where she’s from, and being exposed to a world that is so vast and full of so many distinct characters and settings gives her the courage to accept the things about herself that make her unique.

I think what most excites me about writing these kinds of books is that I get to write about a character who looks and thinks like 13-year-old me. Fantasy books about African American kids just didn’t exist when I was growing up. And that meant that whenever I would imagine a fantasy world, I would immediately remove myself because I had subconsciously accepted that I couldn’t exist there. And the same was true when I started writing fantasy—I truly believed that there were some adventures that Black kids just didn’t get to have. I’m so grateful to folks in publishing like Rick Riordan who put minority characters and their cultures front and center and really opened the door for every kind of kid to be the hero of their own story. And not only that, but these stories promote and shine a positive light on the wonderful cultures that mean so much to us as minorities and make us who we are. So many kids today get to see themselves reflected in the book covers, and it’s a positive affirmation that ‘your stories matter’ too.

The Enchanted Life of Valentina Mejía

Alexandra Alessandri (Atheneum, out now)

Editor Sophia Jimenez: Alessandri turns mythical creatures into endearing individual characters and describes the landscapes of Colombia so vividly that I felt at home in the world of the novel, despite not having grown up with those particular stories myself.

Alessandri: Part of what drew me to write this kind of fantasy adventure is the fact that I wish I’d had these books as a child, ones that featured my culture in such an unapologetic manner that didn’t repeat the stereotypes surrounding Colombia, and ones that featured Colombian characters having magical adventures like those in the Chronicles of Narnia.

For me, cultural representation goes hand-in-hand with a deep sense of place, so one of the first things I did was look inward toward the myths and legends from my childhood, but also to the places in Colombia I knew and loved. Then I began researching both because memory and family lore can only give you so much. I needed to dig deeper to understand these myths and legends, as well as what they represented within the larger context of my culture, how they embodied the pain and violence but also the joys that are woven into Colombia’s history and people. Through those details, I was able to bring the legends and world to life.

Juniper Harvey and the Vanishing Kingdom

Nina Varela (Little, Brown, out now)

Editor Alexandra Hightower: In middle grade, it’s crucial that stories don’t talk down to kids, but instead speak directly to them and meet them where they are. Nailing this voice means more than aging the character between 8-12, it’s about seeing the world through a tween’s eyes, capturing the enthusiasm, the angst, the anxieties, and the hope that they feel when moving through life. For example, in Juniper Harvey and the Vanishing Kingdom, author Nina Varela leans into a first-person perspective that includes just the right edge of self-deprecation. This vulnerability welcomed me into the messiest parts of Juniper’s heart, and this closeness and authenticity allows readers to really feel the way Juniper grows into herself by the end.

Varela: Juniper Harvey is inspired by the story of ‘Pygmalion the Sculptor,’ first recorded in Ovid’s Metamorphoses—a chronicling and reworking of existing myths and legends that had long been floating in the Greco-Roman cultural soup. Princess Galatea’s culture is based on the Classical period of Ancient Greece and informed by the Greek pantheon, but her gods have different names, different histories. I approached it research-first, rereading a lot of classical texts—and researching lesbians and lesbian expression in antiquity, starting with Sappho and going from there. Greek mythological retellings are hardly underrepresented in Western literature—I’m not breaking new ground, structuring my pantheon off the Theogony. Mostly I took the story of Pygmalion the woman-hating sculptor—the artist whose beloved creation came to life—and made it about young queers. I think this is at least slightly in the spirit of Ovid, obsessed as he was with metamorphosis—and the transformation of traditional narratives to suit his preferences.

I had so much fun with the magic. From one draft to the next I pulled fewer and fewer punches, just going all-out—yes Galatea’s island floats in the sky, yes there are fanged flying sheep and toady swamp creatures and lesbian gods…. I just wanted it to feel so big and wild. I also wanted to play with the portal fantasy genre’s emphasis on place—of course Galatea’s world feels magical, but I wanted Juniper’s world (small-town Florida) to feel magical too. I didn’t want our world to be the boring gray-wash one. The existence of Actual Magic isn’t what makes a place magical—it’s how much attention you pay to the wondrous workings of it, how much you’re willing to notice. If you decide it’s beautiful then it is. I wanted to make Juniper’s home beautiful.

I hope this book feels like an escape. Especially for queer readers. Again, it’s set in Florida—the state that in March 2022 passed the so-called “Don’t Say Gay” law prohibiting public school teachers from instructing on sexual orientation or gender identity in kindergarten through third grade. Florida lawmakers are currently trying to expand those restrictions through eighth grade. In the U.S., more than 300 new anti-LGBT bills were introduced in 2022 alone. We’re in the midst of a full-blown moral panic about transness, especially the existence of trans kids—virulent, horrific, increasingly violent transphobia is coming from all sides. Conservatives are calling for ‘eradication’ of trans people. Liberals are hemming and hawing, too cowardly as always to condemn even the most blatant calls for genocide. It is reprehensible beyond words. Queer kids deserve so much better. I want joy and safety, comfort and acceptance, for them, as much as they can get; as much as I can give.

I hope this book feels like an escape. Especially for queer readers, I want joy and safety, comfort and acceptance for them, as much as they can get, as much as I can give.

Lei and the Fire Goddess

Malia Maunakea (Penguin Workshop, June)

Editor Elizabeth Lee: Lei and the Fire Goddess is Malia Maunakea’s debut novel, and actually the first book I acquired at Penguin Workshop. It’s about a part-Hawaiian girl who accidentally angers Pele the fire goddess and must now battle mythical creatures, team up with demigods and talking bats, and evade the traps Pele hurls her way. It’s also about Lei’s insecurities about her hyphenated identity, and subsequently, her middle-school friendships. I won’t spoil the ending, but Lei needs to really dig deep into her Hawaiian roots and embrace all of who she is to save the day. It’s a fast-paced, lush, exciting read—and it’s one of the first middle-grade Hawaiian titles to be published by a major publisher. I truly cannot wait for readers to meet Lei in June.

Maunakea: I love exploring the idea that the world isn’t always quite what it seems—it can be bigger and brighter and hold more than we are aware of—and that individuals are capable of greatness.

One of the best parts of writing Lei and the Fire Goddess was that it gave me a reason to revisit all the moʻolelo—the myths, legends, and history—that I grew up with in Hawaiʻi. To remember what I learned from my teachers in Hilo. To fill the story with as much of the flavor of the islands as I possibly could by recalling sounds and smells of the rainforest, by picturing our ʻohana potlucks, and by attempting to bring the legends that I’ve admired for decades, represented in so many of Herb Kane’s paintings, to life.

With these stories I’m trying to provide three things. First, I want to provide a story with ideas that readers from any number of backgrounds might identify with. The struggles of not fitting in, not feeling ‘enough,’ losing and gaining friends, doing what is right after making mistakes—these themes are universally resonant and relatable.

Second, I’m trying to create a story that is engaging and exciting for the readers who see themselves reflected in the pages for the first time. I don’t want to spend time explaining each of the Hawaiian words, common foods, or customs. This should feel like home to them, someplace where they feel like they can leave their slippers by the door, come on in, and be nodding along as they read.

Last but no less important, I want to provide a window for readers who may have never visited the islands or who only are familiar with the postcard-perfect paradise and want a peek behind the glossy magazine pages to learn more. I bring these readers along on the adventure, utilizing context clues to encourage them to hang on and expand their viewpoints.

Momo Arashima Steals the Sword of the Wind

Misa Sugiura (Labyrinth Road, out now)

Editor Liesa Abrams: Momo learns she is half-goddess and must embark on a wild adventure in order to save her mother’s life, as well as to prevent evil spirits from wreaking havoc on our world.

Sugiura: I wanted to write something for [my sons] in their favorite genre that would also serve as a way for them to connect to their Japanese heritage. For starters, I decided to base the book on stories from the Shinto pantheon rather than Buddhist stories because Shinto is a native Japanese religion (as opposed to Buddhism, which arrived in Japan in 538 C.E. by way of China). But when I looked for models and source material in English, I discovered that there were no modern collections or stand-alone retellings of Shinto stories (for children or even for adult academics) available in the United States. In fact, the only text I could find was a hundred-year-old translation of the very first written record of those stories from 1,500 years ago! So what began as a desire to give my sons a connection to my parents’ homeland became a desire to share Shinto stories with the rest of the world.

What I am really excited about—aside from writing fight and chase scenes, which I adore—is letting readers experience and explore topics and feelings through the safety of this imaginary world. I’m also excited for readers to meet a slightly different kind of heroine—someone who’s anxious and awkward rather than naturally intrepid and quick-witted—and to see her grow into herself.

I hope that everyone will get swept up in the action and the world—the fantasy of it all—but I also hope they will feel seen by Momo’s observations on her status as a misfit and an outsider. I hope there are readers out there who will identify with Momo’s burdens as a kid who has to take care of their parent, or as a kid who struggles with how to express their pent-up anger and frustration, or even as a kid who feels hurt by their best friend moving on to a “cooler” friend group.”

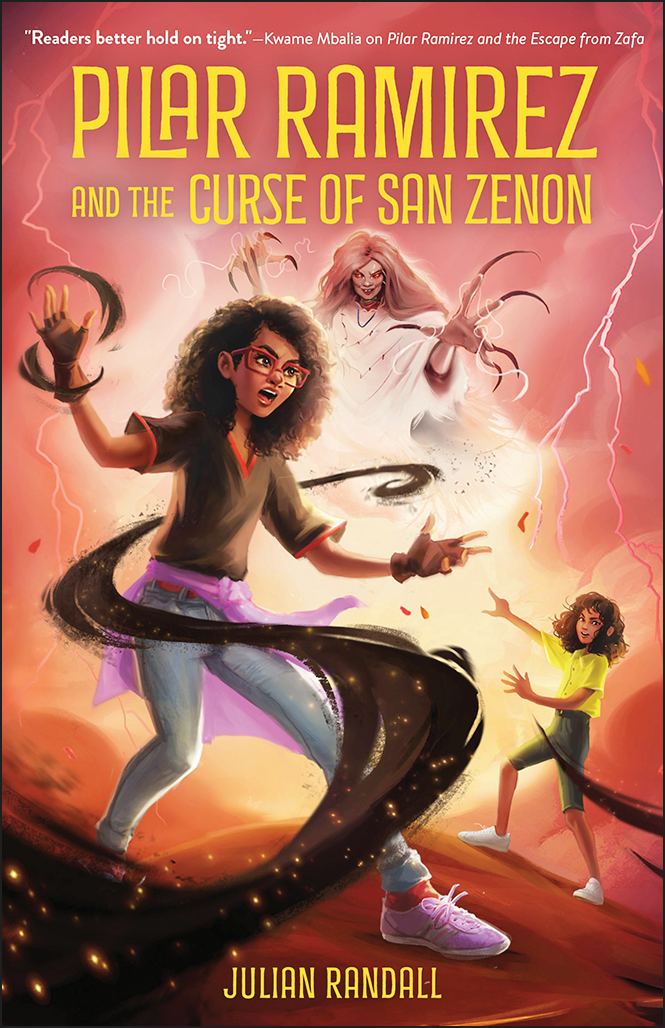

Pilar Ramirez and the Curse of San Zenon

Julian Randall (Holt, out now)

Editor Brian Geffen: Julian Randall’s Pilar Ramirez duology is best pitched as The Land of Stories meets Dominican mythology and culture. The story follows 12-year-old Pilar, who is searching for the story behind her mom’s cousin who went missing in the Dominican Republic during the Trujillo dictatorship, and ends up being accidentally transported to a magical island filled with Dominican myths and legends, where the Dominican boogeyman is keeping her cousin captive.

Randall: When I was eight years old my mom explained the story of how my abuelo had to flee the Dominican Republic because of targeting by Trujillo’s secret police, and in my mind this was something that could have only been accomplished with bad magic. Dictatorship is a kind of sorcery; I wanted a book that showed all the other magic that fights back against it. I wanted a Black Dominicana heroine who could shatter a curse like that; I wanted it for 20 years and then along came Pilar.

My goal was to write a book that highlighted and praised the magic of one’s own childhood and the ways our varying identities and backgrounds give us access to such different magics and that that should be celebrated! Magic doesn’t exist to be homogenized, it’s a long playlist in many languages to an even longer party and I want every kid to feel like there’s a song waiting for them inside these books.

I want readers of Pilar, of all my books, to feel like there are innumerable worlds in which they are powerful, brilliant, celebrated, and most importantly free and loved. My goal is for young readers to pick up these books, see their faces on the cover, hear their loved ones in the dialogue, and feel that music in their bones. I want them to feel like they can be what saves them.

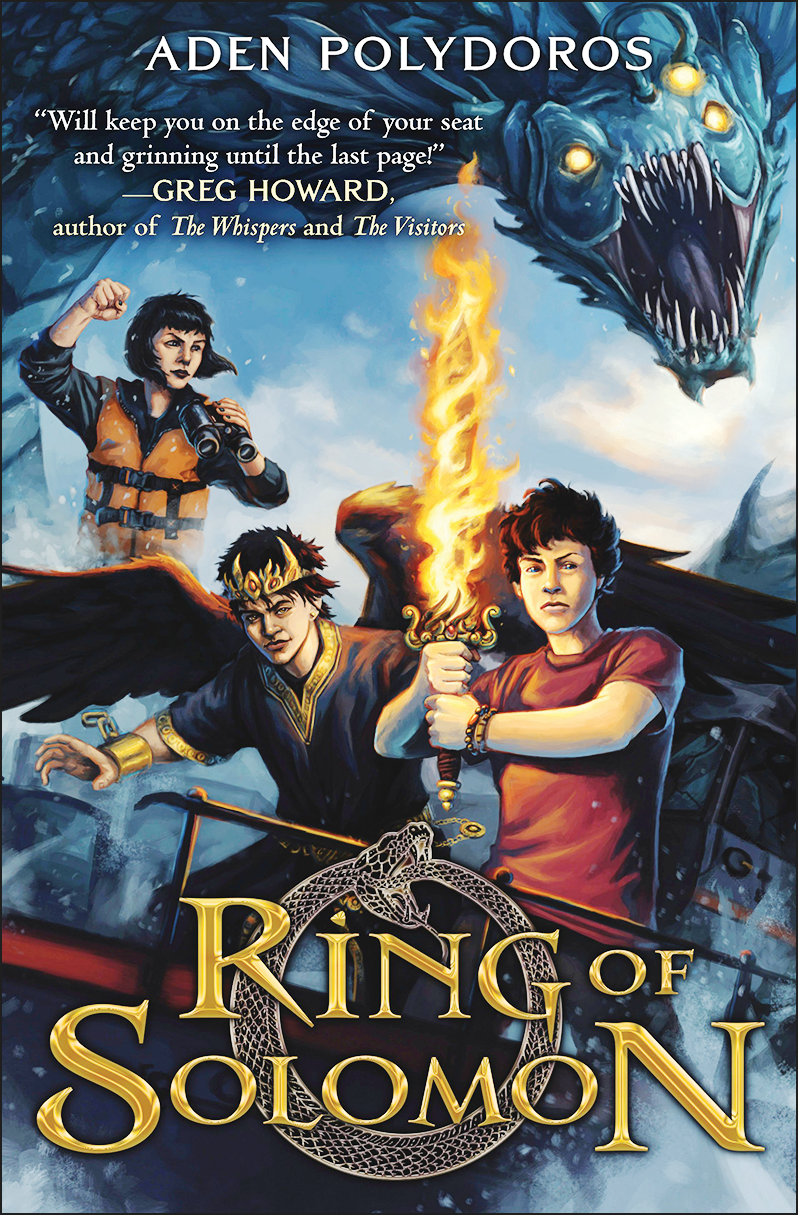

Ring of Solomon

Aden Polydoros (Inkyard, out now)

Editor Meghan McCullough: Ring of Solomon is lush with Jewish mythology; it centers on Zach, a queer Jewish boy who, at a flea market, stumbles upon a mysterious ring that belonged to King Solomon. Using the ring, and with the help of Ashmedai—in Jewish lore, the King of Demons—Zach must halt apocalyptic chaos as the Behemoth, the Ziz, and the Leviathan descend upon his hometown.

Polydoros: I adore stories that draw from mythology and folklore, both as a reader and a writer. For me, I knew I wanted to write a Jewish fantasy. With The City Beautiful (Inkyard, 2021) exploring dybbukim, possessive spirits in Jewish folklore, and my forthcoming Wrath Becomes Her (Inkyard, 2023) featuring a golem protagonist, I pondered the idea of writing a novel about shedim. Through my initial research, I read about the fabled ring of Solomon, and from there, the idea took on a life of its own.

As for cultural representation, it was important for me to write a character who, like me, comes from an interfaith family and is nonobservant. I wanted to show readers that they can be Jewish and still be secular or feel estranged from their religion, and that shouldn’t exclude them from going on adventures.

I feel like middle grade queer adventure stories are so important right now for young LGBTQ+ readers. With increasingly fascist rhetoric and legislation targeting the LGBTQ+ community, and an unprecedented wave of transphobic bills and book bannings, queer youth need stories where they can be the heroes and save the day. I’m excited that my book came out now, in a time when I feel it’s needed most.

For some readers I’m hoping this will be a spark of representation they can treasure. For others, I hope that reading this book from Zach’s POV will allow them to see the humanity in their Jewish and queer classmates and prevent some of the same antisemitic and homophobic bullying I endured as a child. For readers in general, I hope it’ll make them laugh, gasp, and stay up all night reading.

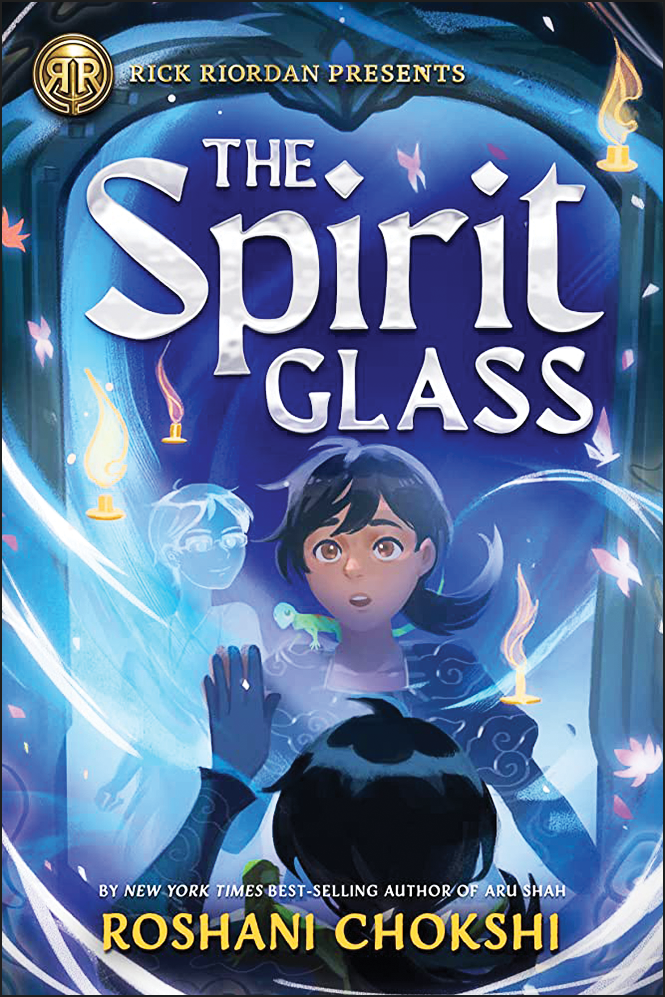

The Spirit Glass

Roshani Chokshi (Rick Riordan Presents, Sept.)

Editor Stephanie Owens Lurie: The Spirit Glass is a standalone novel based on Filipino mythology from Roshani Chokshi, author of the bestselling Aru Shah series. It is the story of a girl named Corazon Lopez who wants to be trained in babaylan magic so she can keep her ghost parents with her forever. The book has all the humor and imagination of Aru Shah plus a deeply moving core.

Chokshi: I’ve always been drawn to adventures that are vaguely spooky and comically unsettling. I am scared of ghosts, but delighted by the idea of a ghost that refuses to haunt a particular house because it objects to the interior decorating. That’s not a story I’ve written—though someone is welcome to make it their own—but it’s this contradictory tension of fear and fun that delights me as a reader and artist, Spirit Glass was always intended to explore a world that existed in the shadowy place between life and death. And it was always intended to remove horror from that situation.

It’s a very enriching and almost sacred experience to explore something that already exists inside you. I was raised on Hindu mythology and Filipino folklore. Those myths and stories have, for better or worse, carved the terrain of my imagination since I was a child. I approached them the way I would with any memory: with a great deal of tenderness for what it meant to me personally and the weighted wariness of acknowledging what those stories mean to others.

The thing that makes writing this kind of book for middle graders especially enjoyable for Chokshi is “the unknown. I set out with the idea that Spirit Glass would be another high-adrenaline, joyous mythological dive in the vein of Aru Shah, but the book quickly took on a life of its own. It became softer, solemn, weighted. It was the rare draft that emerged polished, having already known from the very beginning what it wanted to be and defying my outline at every turn. That is what excites me—that even when we have a premise, a plot and a protagonist, what is otherwise a lifeless litany of ideas alchemizes into magic and transforms into a book that I do not simply want to read but need to write.

Additional Titles

The following is a selected listing of current middle grade fantasy adventures.

Adia Kelbara and the Circle of Shamans by Isi Hendrix (Balzer + Bray, Sept.)

Editor Kristin Rens: “Inspired by Isi’s own Nigerian heritage, and by Nigerian folklore, it’s the first in a debut Afrofantasy trilogy about a girl who’s been told all her life that she’s an ogbanje, a demon-possessed child who brings misfortune wherever she goes. So she accepts an apprenticeship at the magical Academy of Shamans, hoping someone there can ‘fix’ her. Once there, of course, she finds that the academy is not all it seems to be—and she must join forces with a snarky Goddess and a 500-year-old warrior girl to travel through hidden realms to save her kingdom. It’s an edge-of-your-seat adventure that’s also a story about questioning what you’ve been taught to believe about both your world and yourself.”

Charlie Hernández series by Ryan Calejo (Aladdin, Book #4 due in fall 2023)

Normal kid Charlie gets swept up in an ancient battle when the creatures from Hispanic lore that his abuela told him about begin to manifest in his life—and he discovers his destiny as a demon slayer.

Farrah Noorzad and the Ring of Fate by by Deeba Zargarpur (Labyrinth Road, summer 2024)

Editor Liesa Abrams: “Farrah Noorzad and the Ring of Fate is a fantasy story inspired by elements of Persian and Islamic mythology, rooted in one girl’s wish to finally know her absentee father.”

Madsi the True by S. J. Taylor (Atheneum, fall 2024)

Editor Sophia Jimenez: “It’s a historical fantasy adventure set in 1700s Norway that draws on Scandinavian mythology. Madsi believes her sister was stolen by the Northern Lights, but to find out the truth, she must leave home and question everything she believes—fighting Norse monsters and meeting some wonderful new friends along the way. A lot of people are familiar with the Norse gods, but this story focuses on Scandinavian mythical creatures and history that might be new to a lot of U.S. readers.”

The Marvellers by Dhonielle Clayton, (Henry Holt, 2022)

Editor Brian Geffen: “It’s a middle-grade series about a magic school in the sky where kids from all over the world come to study different cultural arts. It follows young Ella, who is a conjuror, and practices different magic than marvellers, and so she must navigate the ups and downs of being the first conjuror admitted to the prestigious Arcanum Training Institute—and soon finds herself going toe-to-toe with an escaped, magical criminal.”

The Pearl Hunter by Miya T. Beck (Balzer + Bray, Feb.)

Beck’s debut fantasy set in a world inspired by Japanese mythology, in which a young pearl diver strikes a supernatural bargain and braves a perilous mission to save her twin sister who’s been stolen by a ghost whale.

The Scroll of Chaos by Elsie Chapman (Scholastic, Mar.)

Twelve-year-old Astrid discovers a magic Chinese scroll that transports her and her younger sister to a realm where Chinese legends are real—and where Astrid must stop an ancient evil.

Serwa Boateng’s Guide to Wtichcraft and Mayhem by Roseanne A. Brown (Rick Riordan Presents, Sept.)

Editor Stephanie Owens Lurie: “Continues Brown’s series based on Ghanaian mythology. Readers left breathless by the cliffhanger ending of Serwa Boteng’s Guide to Vampire Hunting will get to see the preteen Slayer in a whole new light as she learns a shocking truth about her identity”.

Winston Chu vs. the Whimsies by Stacey Lee (Rick Riordan Presents, Feb.)

Editor Lurie: “Stacey Lee’s wild romp inspired by a Chinese folktale. When a boy named Winston stumbles into an oddities shop in San Francisco, the owner tells him he must take home the first thing he touches. Winston ends up with a dustpan and broom that sweep some of his favorite things out of his life—including his baby sister!”

Volume 270

Issue 12

03/20/2023

Volume 270

Issue 12

03/20/2023